What is Director and Officer Liability for Charities in Canada?

In Canada, individuals who serve as directors and officers for charities play a vital role in ensuring the organization runs smoothly and adheres to legal and ethical guidelines. However, many people don't realize that these roles come with potential personal liabilities. Understanding director and officer liability is crucial for anyone involved in running a charity, as failure to comply with regulations can lead to personal legal consequences.

Who Are the Directors and Officers?

Directors are the individuals who sit on the board of a charity. They are responsible for making high-level decisions, setting policies, and overseeing the organization's activities. Officers, on the other hand, are typically appointed by the board to handle the charity's day-to-day operations, such as a CEO, CFO, or Executive Director.

In many cases, directors and officers are volunteers who serve out of passion for the cause. However, the responsibilities they carry can put them at risk for personal liability if the organization fails to comply with the law.

Director Requirements in Canada

Under Canadian law, charities must meet specific requirements for their boards:

- Federally incorporated charities under the Canada Not-for-Profit Corporations Act (CNCA) must have a minimum of three directors

- Directors must be at least 18 years old and mentally capable

- Federal charities under the CNCA do not have a Canadian residency requirement for directors—boards can be composed entirely of non-residents

- Directors should not be bankrupt or have been convicted of fraud-related offences

- Directors are typically elected by members for specified terms (commonly one to three years)

Understanding these basic requirements helps ensure your charity board is properly constituted from the start, reducing the risk of governance issues that could lead to liability.

The Legal Obligations of Directors and Officers

Directors and officers must fulfill several legal duties under Canadian law:

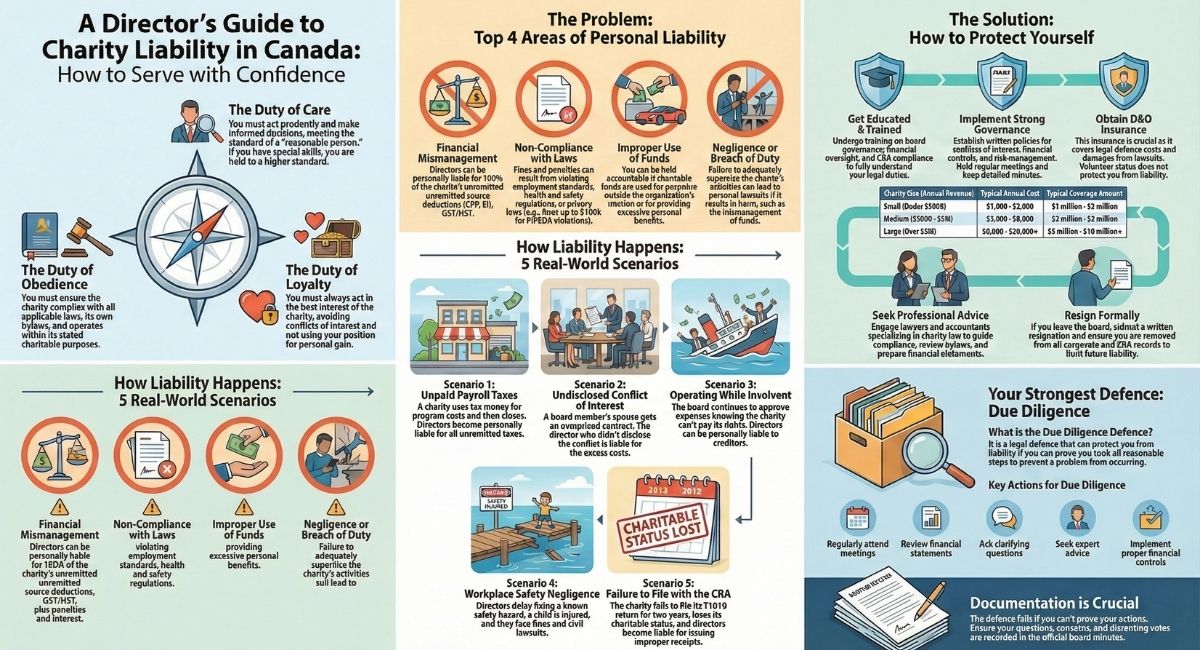

1. Duty of Care

Directors and officers must act prudently and diligently, meeting the standard of a "reasonable person" in similar circumstances. It's important to note that if a director possesses special skills or expertise—such as being a lawyer, accountant, or financial professional—they may be held to a higher standard than a layperson under Ontario common law. This means they must make informed decisions and consider the best interests of the charity at all times.

What this looks like in practice:

- Attending board meetings regularly and preparing beforehand by reviewing materials

- Asking questions and seeking clarification on matters you don't understand

- Staying informed about the charity's financial position and operations

- Hiring qualified professionals (accountants, lawyers) when expertise is needed

- Reviewing financial statements and ensuring proper oversight

- Exercising independent judgment, not simply rubber-stamping management decisions

- If you have professional expertise, applying that expertise appropriately to charity matters

For example, a director should attend board meetings regularly and actively participate in decision-making. If a director consistently misses meetings or fails to review financial reports, they may be found to have breached their duty of care. Additionally, a director who is a chartered accountant would be expected to apply their financial expertise when reviewing the charity's financial statements.

2. Duty of Loyalty

They must avoid conflicts of interest and always put the charity's interests first. This duty requires directors to act honestly and in good faith.

What this looks like in practice:

- Disclosing any personal or business relationships that could create conflicts

- Abstaining from voting on matters where you have a conflict of interest

- Not using your position for personal gain or to benefit family members

- Maintaining confidentiality of board discussions and sensitive information

- Not competing with the charity or taking business opportunities meant for the charity

For instance, if a director has a business that could benefit from a charity's decision, they must disclose this conflict and avoid participating in related decisions. If a director's company is being considered as a vendor, that director must leave the room during discussions and votes.

3. Duty of Obedience

Directors and officers must ensure the charity complies with all applicable laws and regulations, including maintaining its charitable status. This involves following the rules set by federal and provincial governments as well as adhering to the charity's bylaws.

What this looks like in practice:

- Ensuring the charity operates within its stated charitable purposes

- Following the charity's bylaws, policies, and governing documents

- Complying with the Income Tax Act requirements for registered charities

- Meeting filing deadlines for the T3010 Annual Information Return

- Ensuring proper use of charitable donations

- Keeping accurate books and records

A breach of this duty might occur if directors allow the charity to engage in activities outside its charitable objects or fail to ensure CRA filing deadlines are met.

What Can Directors and Officers Be Liable For?

There are several areas where directors and officers can face personal liability if the charity does not meet its legal obligations:

1. Financial Mismanagement

Directors and officers may be held personally liable for unpaid taxes, including GST/HST, or for failing to remit employee payroll deductions. For example, if a charity does not send the appropriate tax payments to the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), directors could be personally responsible for the debt.

Under the Income Tax Act and Excise Tax Act, directors can be held personally liable for:

- 100% of unremitted source deductions (income tax, CPP, EI) from employee wages

- Unremitted GST/HST collected but not paid to the CRA

- Penalties and interest that accumulate on these amounts

This liability can extend to directors who were on the board when the amounts should have been remitted, even if they've since resigned.

2. Non-Compliance with Laws

Charities must adhere to a range of federal and provincial regulations, including those related to employment, privacy, and health and safety. If the charity violates these laws, directors and officers may face fines or other penalties.

Specific areas of potential liability include:

- Employment standards violations: Unpaid wages, improper terminations, failure to provide minimum employment standards. Under the CNCA and ONCA, directors can be held liable for up to six months of unpaid wages to employees, but only if the claim is initiated while they are a director or within two years of leaving the board.

- Occupational health and safety: Workplace injuries due to unsafe conditions can result in fines ranging from $1,500 to $1.5 million depending on the severity

- Privacy breaches: Violations of PIPEDA or provincial privacy laws can result in fines up to $100,000 per violation

- Environmental violations: If the charity owns property, directors may be liable for environmental contamination or violations

- Accessibility legislation: Failure to comply with accessibility requirements under federal or provincial laws

3. Improper Use of Charitable Funds

Directors and officers must ensure that funds are used for the charity's stated mission. If funds are misused, such as being spent on activities unrelated to the charity's objectives, directors could be held accountable.

The CRA can revoke a charity's registration if funds are not used for charitable purposes. Directors may face personal liability if they:

- Approve transactions that benefit themselves or related parties without proper disclosure

- Allow excessive compensation to staff or board members

- Permit the charity to make gifts to non-qualified donees

- Fail to maintain adequate direction and control over funds given to other organizations

4. Negligence or Breach of Duty

Directors can be held liable for failing to meet their duties of care, loyalty, or obedience. For example, if a director fails to supervise the organization's activities and this leads to harm (such as mismanagement of funds), they could face personal lawsuits.

Real-World Liability Scenarios for Charity Directors

Understanding how liability occurs in practice helps directors recognize and avoid risky situations. Here are common scenarios where Canadian charity directors have faced personal liability:

Scenario 1: Failure to Remit Payroll Deductions

A small charity experiences cash flow problems. The treasurer decides to delay remitting employee source deductions to the CRA to pay for an urgent program expense. The charity eventually runs out of money and closes. Result: All directors serving during the period when deductions weren't remitted can be held personally liable for the full amount, plus penalties and interest—potentially tens of thousands of dollars per director.

Scenario 2: Related-Party Transaction Without Disclosure

A board member's spouse owns a catering company. The board approves a contract with this company without the board member disclosing the relationship or abstaining from the vote. The contract terms are later found to be above market rate. Result: The board member who failed to disclose could be liable for the excess costs, and other directors who approved without questioning could be liable for breach of their duty of care.

Scenario 3: Operating While Insolvent

A charity's board knows the organization owes $50,000 more than it can pay, but directors continue approving expenses and signing contracts hoping donations will increase. The charity eventually declares bankruptcy. Result: Directors who continued operations while knowing the charity was insolvent can be personally liable to creditors for debts incurred during this period.

Scenario 4: Workplace Safety Violation

A charity operates a youth camp. Directors are informed of safety concerns about an aging dock structure but delay repairs due to budget constraints. A child is injured when the dock collapses. Result: Directors can face fines under occupational health and safety legislation, and potentially civil lawsuits for negligence. The charity's insurance may not cover director liability if they knew about the hazard and failed to act.

Scenario 5: Charitable Registration Revocation

Directors fail to ensure the charity files its T3010 Annual Information Return for two consecutive years. The CRA revokes the charity's registration. The charity continues to issue donation receipts after revocation. Result: Directors can be personally liable for penalties related to improper receipting, and the charity loses its ability to issue tax receipts permanently, effectively ending its fundraising capacity.

How Can Directors and Officers Protect Themselves?

Understanding the potential liabilities is the first step in protecting oneself as a director or officer of a charity. Here are some practical ways to mitigate these risks:

1. Education and Training

Directors and officers should undergo training to fully understand their legal obligations. Many organizations, like Capacity Canada, provide workshops on governance, compliance, and risk management for charities.

Recommended training topics include:

- Board governance fundamentals

- Financial oversight and reading financial statements

- CRA compliance requirements for registered charities

- Conflict of interest identification and management

- Legal duties and liabilities of directors

- Risk management and insurance

Even experienced business professionals benefit from charity-specific training, as the regulatory environment for charities differs significantly from the for-profit sector.

2. Board Governance Best Practices

It is crucial to establish clear policies and procedures. This involves setting up systems for financial oversight, holding regular board meetings, and maintaining detailed records of decisions.

Essential governance practices include:

- Regular board meetings with proper notice, quorum, and minutes

- Written policies covering conflicts of interest, financial management, human resources, and risk management

- Financial controls including signing authority limits, expense approval processes, and budget monitoring

- Annual planning including strategic plans, budgets, and work plans

- Performance reviews for the Executive Director and organizational outcomes

- Committee structure (finance, governance, fundraising) to ensure proper oversight

- Succession planning to ensure continuity of leadership

3. D&O Insurance

Directors and officers can safeguard themselves from personal liability by obtaining Directors and Officers (D&O) insurance. This insurance type helps cover legal costs and damages resulting from lawsuits or claims of misconduct.

Understanding D&O Insurance for Canadian Charities:

Coverage amounts typically range from:

- Small charities (under $500K revenue): $1 million to $2 million

- Medium charities ($500K-$5M revenue): $2 million to $5 million

- Large charities (over $5M revenue): $5 million to $10 million+

Typical costs:

- Small charities: $1,000-$3,000 annually

- Medium charities: $3,000-$8,000 annually

- Large charities: $8,000-$20,000+ annually

What D&O insurance covers:

- Legal defense costs for lawsuits against directors

- Settlements or judgments (if directors acted in good faith)

- Regulatory investigations and defense costs

- Employment practices liability claims

What D&O insurance typically does NOT cover:

- Intentional illegal acts or fraud

- Personal profit gained through wrongdoing

- Bodily injury or property damage (covered by general liability insurance)

- Unremitted taxes (though defense costs may be covered)

Claims-made vs occurrence policies: Most D&O policies are "claims-made," meaning the policy must be in effect when the claim is made, not when the incident occurred. This makes it crucial to maintain continuous coverage and purchase "tail coverage" if the policy is cancelled.

4. Legal and Financial Expertise

It is advisable for charities to involve legal and financial professionals who can offer guidance on complying with federal and provincial laws. This includes regular audits and legal reviews to ensure the charity is fulfilling all its obligations.

Consider engaging:

- Charity lawyer: For incorporation, bylaw reviews, CRA compliance, and governance advice

- Accountant or bookkeeper: For financial statement preparation, T3010 filing, and tax compliance

- Auditor (if required by your jurisdiction or donors): For annual financial statement audits

- HR consultant: For employment contracts, policies, and workplace compliance

While professional fees are an expense, they're far less costly than dealing with compliance violations or personal liability claims.

5. Conflict of Interest Policies

Implementing a clear conflict of interest policy can help prevent situations where directors or officers could be liable for decisions that benefit themselves over the charity.

A strong conflict of interest policy should include:

- Annual disclosure requirements where all directors declare potential conflicts

- Meeting-by-meeting disclosure at the start of each board meeting

- Clear process for handling conflicts when they arise (disclosure, leaving the room, abstaining from votes)

- Definition of related parties (family members, business associates, other organizations where you serve)

- Documentation requirements ensuring all disclosures and abstentions are recorded in minutes

- Approval thresholds for related-party transactions requiring higher scrutiny

6. Understanding Director Remuneration Rules

In Ontario, directors of charities face strict limitations on remuneration under the Charities Accounting Act. Directors cannot be paid for their services as a director, nor can they be employees of the charity they direct, unless they:

- Obtain a court order authorizing the payment, or

- Follow the specific requirements under Regulation 463/10 for payments to persons "connected" to the charity

This is a critical liability risk—if a director receives a salary or other compensation without proper authorization, they may be required to repay those amounts and could face additional penalties. Directors should consult with legal counsel before accepting any form of remuneration from the charity.

When Does Director Liability Begin and End?

One of the most misunderstood aspects of director liability is the timeline—when you become liable and when that liability ends.

When Liability Begins

Director liability begins the moment you are appointed or elected to the board, even if:

- You haven't attended your first board meeting yet

- You didn't know you were appointed

- You're a "nominee director" representing another organization

- You're serving in an honorary capacity

- You never signed formal acceptance documents

If your name appears on corporate records or CRA filings as a director, you can be held liable for decisions made during your tenure.

When Liability Ends

Director liability does not automatically end when you leave the board. The timing depends on the type of liability:

For most liabilities:

- Liability can continue for up to two years after resignation for certain matters

- You remain liable for actions taken or obligations incurred during your time as a director

For tax-related liabilities:

- Under the Income Tax Act and Excise Tax Act, the CRA must commence an action to hold the director liable within two years of the director ceasing to hold that position

- The CRA must issue a notice of assessment within this two-year window

- However, directors retain due diligence defences during this period if they can demonstrate they took reasonable steps to prevent the failure

For ongoing legal actions:

- If a lawsuit is filed while you're a director (or within limitation periods after you leave), you remain a defendant even if you've resigned

For unpaid wages:

- Under the CNCA and ONCA, directors can be held liable for up to six months of unpaid employee wages

- The claim must be initiated while the person is a director or within two years after they cease to be a director

Importance of Formal Resignation

To protect yourself, always resign formally:

- Submit written resignation to the board chair or corporate secretary

- Ensure resignation is recorded in board meeting minutes

- Confirm removal from corporate filings (verify with the incorporating jurisdiction)

- Check CRA records to ensure you're no longer listed as a director

- Maintain proof of resignation with the date clearly documented

Never assume that simply stopping attendance or verbally stating you've left is sufficient.

The Due Diligence Defence for Directors

While directors face significant potential liabilities, Canadian law provides a crucial protection: the due diligence defence. This defence can protect directors from liability if they can prove they acted responsibly and took reasonable steps to prevent the problem.

What Is the Due Diligence Defence?

The due diligence defence allows directors to avoid liability by demonstrating that they:

- Exercised the degree of care, diligence, and skill that a reasonably prudent person would exercise in comparable circumstances

- Took positive steps to prevent the violation or failure

- Had reasonable grounds to believe their actions were sufficient

This defence is particularly important for tax remittance liabilities, regulatory violations, and statutory obligations.

What Counts as Due Diligence?

Courts consider whether directors took "reasonable steps," which may include:

Financial oversight:

- Reviewing financial statements regularly

- Asking questions about the charity's ability to meet obligations

- Ensuring qualified financial personnel are employed

- Requiring regular reports on tax remittances and compliance

Active participation:

- Attending board meetings consistently

- Reviewing meeting materials in advance

- Asking informed questions and seeking clarification

- Ensuring issues are properly addressed before they escalate

Seeking expertise:

- Hiring qualified accountants, lawyers, and other professionals

- Following professional advice when provided

- Obtaining expert opinions on complex matters

Systems and controls:

- Implementing proper financial controls and approval processes

- Establishing policies for tax remittances, payroll, and compliance

- Conducting regular reviews of compliance systems

- Taking corrective action when problems are identified

Documenting Your Due Diligence

The key to successfully using the due diligence defence is documentation. If you can't prove you took reasonable steps, the defence fails.

Essential documentation includes:

- Board meeting minutes showing you attended, asked questions, and raised concerns

- Written questions and responses to management or committees

- Professional advice obtained (legal opinions, accounting advice, audit reports)

- Policies and procedures you helped implement or review

- Evidence of corrective action taken when problems arose

- Training certificates showing you sought education on your responsibilities

Pro tip: If you raise concerns at a board meeting, ensure they're recorded in the minutes. If you disagree with a decision, request that your dissent be recorded. This documentation could be crucial if liability issues arise years later.

When the Due Diligence Defence Does NOT Apply

The defence will not protect you if:

- You were willfully blind to problems (deliberately avoided learning about issues)

- You had actual knowledge of violations and did nothing

- You were grossly negligent in your duties

- You participated in or authorized wrongdoing

- You failed to attend meetings or remain informed

How Do Canadian Laws Affect Charity Directors and Officers?

In Canada, charity directors and officers are subject to both federal and provincial laws, depending on where the charity operates. For example, the Canada Not-for-Profit Corporations Act (CNCA) governs federally incorporated charities, while provinces like Ontario have their own laws, such as the Ontario Not-for-Profit Corporations Act (ONCA). These laws outline the specific responsibilities of directors and officers and the penalties for failing to meet them.

It's important for charity leaders to be aware of which laws apply to their organization. For example, federally incorporated charities must file annual returns with the CRA, while provincially incorporated charities may have different filing requirements. Understanding these differences is key to avoiding penalties and staying compliant.

Federal vs Provincial Incorporation: Key Differences for Directors

Your obligations as a director vary depending on whether your charity is incorporated federally or provincially:

Federal (CNCA) Requirements:

- Minimum three directors required

- At least 25% of directors must be Canadian residents

- Must file annual corporate returns with Corporations Canada

- Must hold annual general meetings

- Financial statements must be prepared annually and made available to members

- Director residency can be waived in certain circumstances

Ontario (ONCA) Requirements:

- Minimum three directors required

- All directors must be at least 18 years old and not bankrupt

- Must file annual returns with the Ontario Business Registry

- Must hold annual general meetings (with some exceptions for non-soliciting corporations)

- Financial review, audit, or compilation required depending on revenue and member requests

- Specific transition deadlines for charities incorporated before ONCA came into force

- Directors subject to remuneration restrictions under the Charities Accounting Act

British Columbia (Societies Act) Requirements:

- Minimum three directors required

- Majority of directors must be Canadian residents or permanent residents

- Must file annual reports with BC Registry Services

- Must hold annual general meetings

- Financial statements must be prepared and presented at AGM

- Different financial reporting thresholds than other jurisdictions

Quebec (Civil Code and Quebec Companies Act):

- Different legal framework from other provinces

- Specific requirements for language of corporate documents

- Unique governance requirements under Quebec law

Filing Deadlines and Penalties

Missing filing deadlines can result in personal liability for directors:

Federal charities (CNCA):

- Annual return due within 60 days of anniversary of incorporation

- Late filing can result in penalties and potential dissolution

- Directors personally liable for ensuring compliance

Ontario charities (ONCA):

- Annual return due within 60 days of fiscal year-end

- Failure to file can result in administrative dissolution

- Directors must sign off on annual returns in some cases

All registered charities (CRA):

- T3010 Annual Information Return due within 6 months of fiscal year-end

- Failure to file for two consecutive years results in automatic revocation

- Directors responsible for ensuring timely, accurate filing

Understanding your specific obligations based on your jurisdiction prevents costly compliance failures.

Conclusion

Serving as a director or officer for a charity in Canada is a rewarding experience, but it comes with significant responsibilities and potential liabilities. Directors and officers must fulfill their legal duties of care, loyalty, and obedience, ensure compliance with both federal and provincial laws, and protect the charity's resources from misuse.

The good news is that liability risks can be managed effectively through education, proper governance practices, professional advice, and appropriate insurance coverage. By understanding your obligations, documenting your due diligence, and implementing strong oversight systems, you can serve your charity with confidence while protecting yourself from personal liability.

Remember these key protection strategies:

- Stay informed and educated about your responsibilities

- Attend meetings and remain actively engaged

- Ask questions and seek professional advice when needed

- Ensure proper financial controls and oversight systems

- Maintain comprehensive documentation of board activities

- Obtain adequate D&O insurance coverage

- Understand remuneration restrictions if serving an Ontario charity

- Resign formally if you choose to leave the board

By staying informed, implementing best practices, and securing appropriate insurance, charity leaders can minimize their risk and continue to support their cause with confidence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can volunteer directors be held personally liable in Canada?

Yes. Volunteer status does not protect directors from personal liability. Canadian law makes no distinction between paid and unpaid directors—both have the same legal duties and face the same potential liabilities. Whether you're volunteering or compensated, you can be held personally responsible for unremitted taxes, regulatory violations, and breaches of your fiduciary duties. This is why D&O insurance is crucial for all charities, regardless of whether board members are volunteers.

What happens if a charity director resigns—are they still liable?

Yes, directors remain liable for actions taken during their tenure, even after resignation. For most liabilities, you can be held responsible for decisions made or obligations incurred while you served on the board. For tax-related liabilities under the Income Tax Act and Excise Tax Act, the CRA must commence an action within two years after a director ceases to hold that position. For unpaid wages under the CNCA and ONCA, claims must be initiated while the person is a director or within two years of ceasing to be a director, but liability is limited to six months of unpaid wages. Always resign formally in writing, ensure your resignation is recorded in meeting minutes, and verify you've been removed from all corporate and CRA filings.

How much does D&O insurance cost for Canadian charities?

D&O insurance costs vary based on your charity's size, activities, and claims history. Small charities with under $500,000 in revenue typically pay $1,000-$3,000 annually for $1-2 million in coverage. Medium-sized charities ($500K-$5M revenue) pay $3,000-$8,000 annually for $2-5 million in coverage. Large charities with over $5 million in revenue may pay $8,000-$20,000+ annually for $5-10 million in coverage. The cost is a worthwhile investment compared to potential personal liability, which can reach hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Are directors liable for debts incurred before they joined the board?

Generally, no. Directors are typically only liable for obligations and decisions made during their term of service. However, if you become aware of pre-existing problems after joining the board and fail to address them, you could be liable for allowing those problems to continue. For example, if you discover the previous board failed to remit payroll taxes and you don't take corrective action, you could be held liable for ongoing failures even though the original debt predates your appointment.

Can directors be criminally charged for charity misconduct?

Yes, in serious cases. While most director liability is civil (lawsuits, fines, debt repayment), criminal charges can be laid for fraud, theft, or intentional misconduct. Directors can face criminal charges under the Criminal Code for offences like fraud over $5,000, theft of charitable property, or breach of trust. The CRA can also pursue criminal charges for serious tax evasion or intentional non-compliance. Criminal liability typically requires proof of intentional wrongdoing, not merely negligence or poor judgment.

What's the difference between director and officer liability?

Directors are members of the board who oversee the charity's governance and make high-level decisions. Officers are individuals appointed to specific roles (CEO, CFO, Secretary) who manage day-to-day operations. Both face personal liability, but officers typically have additional responsibilities related to their specific roles. For example, a CFO may have greater liability for financial reporting accuracy, while the board chair may have more responsibility for governance compliance. In practice, many people serve as both directors and officers (called "officer-directors"), carrying both sets of responsibilities.

The material provided on this website is for information purposes only.. You should not act or abstain from acting based upon such information without first consulting a Charity Lawyer. We do not warrant the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site. E-mail contact with anyone at B.I.G. Charity Law Group Professional Corporation is not intended to create, and receipt will not constitute, a solicitor-client relationship. Solicitor client relationship will only be created after we have reviewed your case or particulars, decided to accept your case and entered into a written retainer agreement or retainer letter with you.

.png)