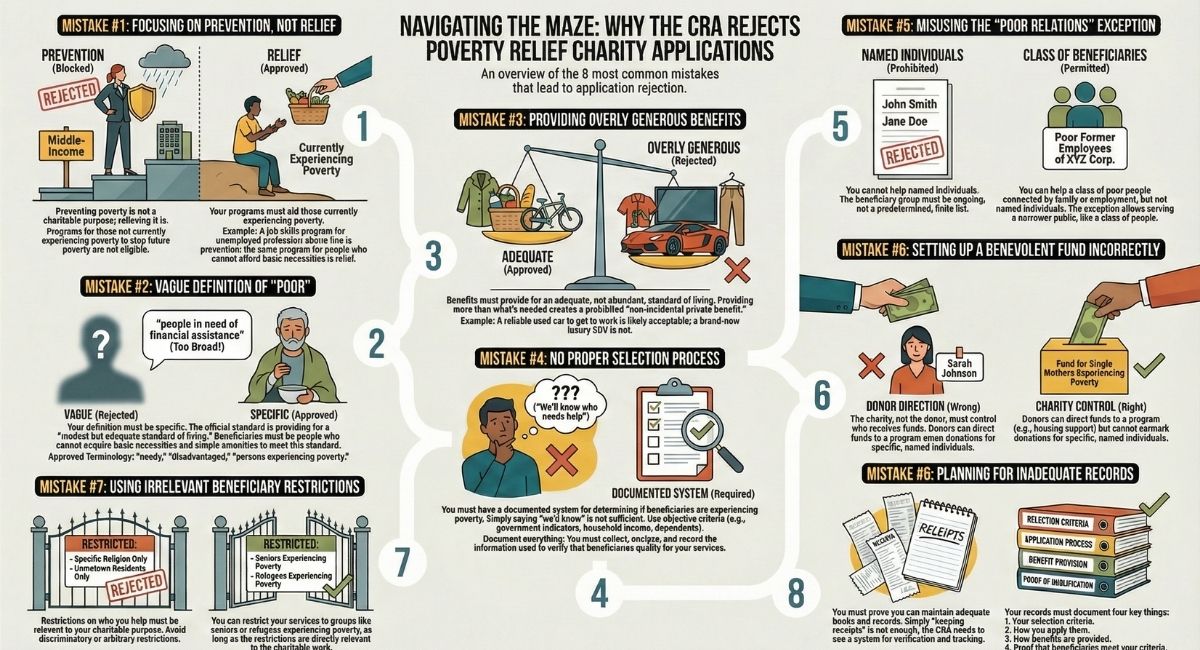

8 Reasons Why the CRA Kicked Your Charity Application to the Curb: Common Poverty Relief Rejections

So, you had a brilliant idea to help people in poverty, filled out all the paperwork, waited with bated breath, and then... rejection. What happened? The CRA's guidance on poverty relief charities reads like a legal textbook, but the reasons applications get rejected often boil down to some surprisingly common mistakes. Let's break down why your noble intentions might have hit a bureaucratic brick wall.

1. You Tried to Prevent Poverty Instead of Relieving It

Here's a head-scratcher: preventing poverty isn't considered charitable, but relieving it is. Think of it this way—you can't register a charity to teach financial literacy classes to middle-income families so they never become poor. That's prevention. However, you absolutely can teach those same classes to people currently experiencing poverty as part of relieving their situation.

The distinction seems pedantic until you realize the CRA is dead serious about it. Your well-meaning "let's stop poverty before it starts" program needs to fit into a different charitable category, like advancement of education. The beneficiaries of educational or community benefit programs don't need to be experiencing poverty, but if your stated purpose is poverty relief, your beneficiaries absolutely must be.

Real-world example: A job skills program for unemployed professionals earning above the poverty line? Not poverty relief. The same program specifically for people experiencing poverty who can't afford basic necessities? That's poverty relief.

2. Your Definition of "Poor" Was Too Vague (or Too Generous)

Saying you'll help "people in need of financial assistance" sounds reasonable, but it's not specific enough for the CRA. The problem? A millionaire going through an expensive divorce might technically need financial assistance, but they're not experiencing poverty.

The courts have established that poverty doesn't mean absolute destitution—it means someone who can't acquire "basic necessities of life and simple amenities that allow for a modest but adequate standard of living." Your application needs to clearly define your beneficiary group as people who genuinely fit this description.

Using terms like "needy," "disadvantaged," or "persons experiencing poverty" works. Using "persons in need of financial assistance" or overly broad language that could include people who are merely cash-strapped? That's a rejection waiting to happen.

3. You Got Too Generous With What Counts as Poverty Relief

Yes, internet access is now considered a basic necessity in Canada. So are home appliances and public transportation. But here's where things get tricky: providing someone experiencing poverty with a reliable used car to get to work? Probably fine. Providing them with a brand-new luxury SUV? Now you're providing more than what's needed for a modest standard of living, which creates non-incidental private benefit—a big no-no.

The same goes for housing. Affordable housing for people experiencing poverty is clearly poverty relief. But if you're putting them up in condos that would make the average Canadian jealous, you've crossed the line from relief into private benefit territory.

Think of it this way: you're helping someone get to adequate, not abundant. The moment your charitable benefits start providing significantly more than what's needed for a modest standard of living, the CRA starts wondering if you're actually a charity or just being really nice to some lucky individuals.

4. You Didn't Have a Proper System for Determining Who's Actually Poor

Let's say you're providing internet access to low-income families. If you're giving it to one family at their home address once, maybe you don't need an elaborate screening process—the risk of accidentally helping someone who doesn't need it is low. But if you're providing expensive items repeatedly, or running an ongoing program with valuable benefits, you absolutely need selection criteria.

Many rejected applications fail because the organization either:

- Has no process for determining if beneficiaries are experiencing poverty

- Has a process, but it's poorly documented

- Uses criteria that don't actually measure poverty

The CRA accepts government poverty indicators like Low-Income Cut-Offs or Market Basket Measures. You can also develop your own criteria, but you need to actually collect and analyze information like household income, number of dependents, employment status, and assets. And crucially, you need to document all of this. Saying "we'll just know who needs help" doesn't cut it.

5. You Violated the "Poor Relations" Exception

This is where things get delightfully confusing. Normally, a charity must benefit a sufficiently broad public. But poverty relief charities get special treatment through the "poor relations" exception—you can help poor members of a family, poor employees of a company, or poor members of certain groups.

However, you cannot help named, specific individuals. The difference? A fund for "poor former employees of XYZ Corporation" can work. A fund for "John Smith and Mary Jones who used to work at XYZ" cannot.

The beneficiary group must be ongoing and not immediately fully known. If you can literally list everyone who might ever benefit by name at the moment your charity starts operating, that's a red flag. The exception exists to help categories of people connected by employment or family ties, not to create backdoor benefits for a predetermined group of individuals.

6. You Set Up a Benevolent Fund the Wrong Way

Benevolent funds are wonderful—they let donors contribute to help specific types of people experiencing poverty. But donors can only give general directions about how their gift should be used within your charitable programs. They absolutely cannot direct funds to named individuals.

Example of doing it wrong: "I'd like to donate $5,000 specifically to help Sarah Johnson with her rent." Nope. That's not a charitable donation; that's a personal gift routed through your organization.

Example of doing it right: "I'd like to donate $5,000 to help with housing costs for single mothers experiencing poverty." Perfect. Your charity then decides which specific beneficiaries receive assistance based on your charitable criteria.

The key principle: all decisions about who gets help must rest with the charity, not the donor.

7. Your Restrictions on Who You'll Help Weren't Relevant to Your Charitable Purpose

You can absolutely restrict your beneficiary group—"women experiencing poverty," "refugees experiencing poverty," "seniors experiencing poverty"—as long as those restrictions are relevant to furthering your charitable purpose and don't violate Canadian public policy.

What you cannot do is add restrictions that are discriminatory or arbitrary. Helping "people experiencing poverty who share my religious views" or "people experiencing poverty from my hometown only" will raise serious questions about whether you're actually serving a charitable purpose or just helping your preferred group.

The restriction must make sense for what you're trying to accomplish. A charity providing culturally specific support services to refugees experiencing poverty? That makes sense. A charity providing generic food hampers exclusively to people from one ethnic background? That's going to be a problem.

8. Your Record-Keeping Plans Were Inadequate

The CRA needs to verify that you're actually helping people experiencing poverty and that your resources are being used for charitable purposes. That means you need to document:

- The selection criteria you use

- How you apply those criteria

- How charitable benefits are provided to beneficiaries

- That those beneficiaries actually meet your criteria for experiencing poverty

Many applications fail because the organization can't demonstrate they'll maintain adequate records. "We'll keep receipts" isn't enough. You need systems to track who you're helping, verify they meet your criteria, and show that the benefits you're providing are appropriate for poverty relief.

The Bottom Line

Getting approved as a poverty relief charity isn't impossible, but it requires precision. You need to clearly define who you're helping, demonstrate they're actually experiencing poverty, provide benefits appropriate for a modest standard of living, have proper selection processes, and maintain good records.

The good news? The CRA has provided detailed guidance with examples of what works and what doesn't. The bad news? You actually have to read it and apply it carefully to your specific situation. Most rejections aren't because the CRA is being unreasonable—they're because applicants didn't understand these specific requirements.

If your application was rejected, look carefully at which of these areas might have been the issue. Often, it's fixable with better documentation, clearer purposes, or more appropriate selection criteria. And if you're just starting out? Taking the time to understand these requirements before you apply can save you months of frustration and reapplication hassles.

After all, the goal is to actually help people experiencing poverty—and you can't do that if you're stuck in bureaucratic limbo.

The material provided on this website is for information purposes only.. You should not act or abstain from acting based upon such information without first consulting a Charity Lawyer. We do not warrant the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site. E-mail contact with anyone at B.I.G. Charity Law Group Professional Corporation is not intended to create, and receipt will not constitute, a solicitor-client relationship. Solicitor client relationship will only be created after we have reviewed your case or particulars, decided to accept your case and entered into a written retainer agreement or retainer letter with you.

.png)