Charitable Bequests in Canada: Giving Through Your Will

At B.I.G. Charity Law Group, we help Canadians navigate the complexities of charitable estate planning to ensure your philanthropic goals are realized while maximizing tax benefits for your estate. Understanding charitable bequests is essential for creating a lasting legacy that reflects your values.

Giving back to causes you care about can continue beyond your lifetime. A charitable bequest lets you support important organizations through gifts specified in your will or estate plan.

Charitable bequests provide substantial tax advantages for your estate while ensuring your favourite causes receive meaningful support long after you're gone. Many Canadians don't realize how flexible these gifts can be.

You can leave money, property, or a portion of what remains after other bequests are paid. Planning a charitable bequest involves understanding Canadian legal requirements and choosing the right beneficiaries.

Work with qualified professionals to ensure your wishes are met. We'll walk you through essential considerations, from provincial differences to tax strategies, so you can make informed decisions about your legacy giving in Canada.

Understanding Charitable Bequests: The Canadian Context

Canadian charitable bequests operate within a legal framework that determines which organizations qualify for tax benefits. The Canada Revenue Agency oversees this system through registered charity requirements.

This framework provides substantial tax advantages for estate planning. Understanding these rules helps you maximize your impact.

Definition And Types Of Bequests

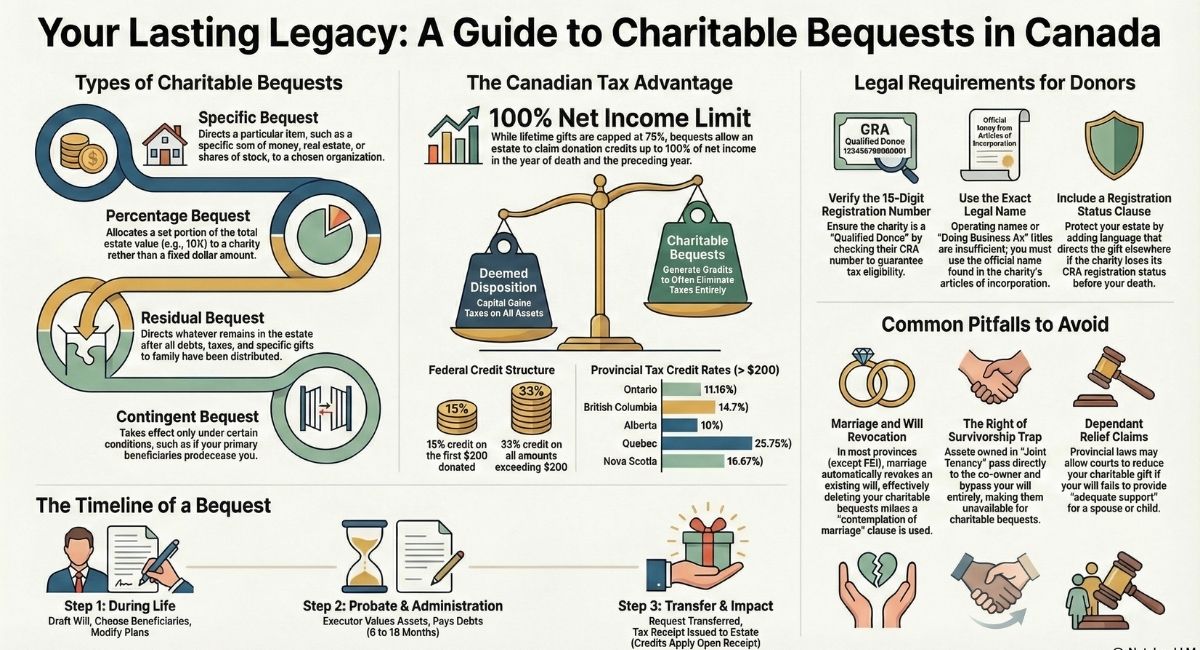

A charitable bequest is a gift you specify in your will that directs part of your estate to a charity after you die. This gift becomes available to the chosen organization without reducing your assets during your lifetime.

You can structure charitable bequests in several ways. Specific Bequests direct a particular item, like stocks, real estate, or valuable property, to your chosen charity.

Percentage Bequests give a set portion of your total estate to charity. For example, you might leave 10% of your estate value to your favourite organization.

Residual Bequests provide what remains after you distribute specific gifts to family and friends. This ensures charities receive something regardless of your estate's final value.

Contingent Bequests only take effect under certain conditions. For example, you might specify that a charity receives funds if your primary beneficiaries predecease you.

Canadian Registered Charities Vs. Qualified Donees Vs. Non-Profit Organizations

Not all organizations qualify for charitable tax benefits in Canada. Understanding these distinctions helps you maximize your bequest's impact.

Registered charities hold official status with the Canada Revenue Agency. These organizations provide full tax benefits for charitable bequests and include most hospitals, religious groups, and community foundations.

Qualified donees include registered charities plus organizations like Canadian municipalities, provincial governments, and certain foreign charities. Bequests to qualified donees generate donation tax credits.

Non-profit organizations without registered charity status don't provide tax benefits. Your estate receives no tax advantages for bequests to them.

Verify an organization's status using the Canada Revenue Agency's list of charities and other qualified donees before including them in your will.

Understanding CRA's Charitable Registration System

The Canada Revenue Agency sets strict requirements for charitable registration. Organizations must demonstrate charitable purposes, provide public benefit, and maintain detailed financial records.

Registered charities receive a registration number and must file annual information returns. They can issue official donation receipt for income tax purposes and must maintain compliance to keep their status.

The CRA reviews charitable status regularly. Organizations can lose registration for non-compliance, which affects their ability to provide tax benefits for bequests.

Confirm current registration status when drafting your will. Use the organization's complete legal name to prevent confusion and ensure your bequest reaches the intended recipient.

Tax Advantages Under The Income Tax Act

Canadian tax law provides significant benefits for charitable bequests. Your estate can claim donation tax credits up to 100% of net income in the year of death.

Any unused credits can apply to the previous tax year. This flexibility often eliminates most or all income taxes your estate might owe.

Capital gains taxes typically apply at death, but charitable bequests of appreciated property often qualify for special treatment. The donation credit frequently offsets these taxes entirely.

These benefits apply only to gifts made to qualified donees. Non-registered organizations don't provide tax advantages.

Donation Tax Credits

Your estate claims charitable bequest credits on the final tax return or the estate's T3 return. The credit equals 15% of the first $200 donated plus about 29% of amounts over $200.

Higher earners may qualify for enhanced credits in some provinces. Combined federal and provincial benefits can exceed 50% of the donation amount.

Credits apply against taxes owed, not total income. The generous limits for death-year donations usually provide full tax relief for most estates.

Professional tax preparation is essential for estates with significant charitable bequests. The timing and calculation of credits require expertise to maximize benefits.

The Deemed Disposition At Death

Canadian tax law treats death as selling all your assets at fair market value. This creates capital gains taxes on appreciated investments, real estate, and business interests.

Charitable bequests help offset these deemed disposition taxes. The donation credits often equal or exceed the capital gains taxes triggered by death.

Direct bequests of appreciated property to charity can eliminate the capital gains entirely in some cases. The charity receives the full asset value while your estate avoids the related taxes.

This strategy works well for highly appreciated stocks, real estate, or business interests that would otherwise create large tax bills.

Timeline: From Intention To Impact

The charitable bequest process begins when you sign your will but doesn't complete until months or years after death. Understanding this timeline helps you plan effectively.

During Life: You draft your will, choose beneficiaries, and can modify bequests as circumstances change.

At Death: Your estate's executor begins probate proceedings and identifies all charitable bequests specified in the will.

Estate Administration: The executor values assets, pays debts, and determines the final bequest amounts. This process typically takes 6-18 months.

Transfer and Tax Benefits: Charitable bequests transfer to organizations after estate settlement. Tax credits apply when the charity receives the gift, not at your death date.

This extended timeline means your chosen charities might wait considerable time before receiving bequests. The tax benefits remain available to your estate.

Before You Begin: Pre-Planning Considerations

Successful charitable bequests require careful planning that balances your financial security, family needs, and philanthropic goals. Understanding tax implications, legal requirements, and professional guidance options will help you make informed decisions about your estate plan.

Assessing Your Estate And Financial Situation

Before adding charitable bequests to your will, you need to understand your complete financial picture. List all assets, debts, and ongoing expenses.

Start by calculating your net worth. Include your home, investments, retirement savings, and personal property. Subtract all debts and liabilities.

Consider your future financial needs. Think about healthcare costs, long-term care, and inflation. These factors affect how much you can comfortably give away.

Key assets to review:

- Primary residence and other real estate

- Investment accounts and RRSPs

- Life insurance policies

- Business interests

- Personal property with significant value

Review your income sources in retirement, including pensions, government benefits, and investment income. Understanding your cash flow helps you determine if you can afford charitable bequests without financial hardship.

Balancing Family Obligations With Philanthropic Goals

Charitable giving should not come at the expense of family financial security. Ensure your spouse and dependents are properly provided for.

Consider your family's current and future needs. Young children may need education funding. Adult children might benefit from inheritance to buy homes or start businesses.

Discuss your charitable intentions with family members. Open communication prevents surprises and family conflicts after death.

Some families choose to involve children in selecting charities.

Options for balancing both goals:

- Leave a percentage to charity rather than a fixed amount

- Set up charitable gifts only after family needs are met

- Use residuary bequests for charitable giving

- Consider smaller charitable amounts with lifetime giving

Family circumstances change over time. Regular estate plan reviews ensure your will reflects current family needs and charitable goals.

Lifetime Giving Vs. Testamentary Gifts: Tax Implications In Canada

Both lifetime giving and charitable bequests offer tax benefits, but the timing differs.

Lifetime charitable gifts provide immediate tax receipts. You can use these receipts to reduce current income taxes. Any unused credits can be carried forward for up to five years.

Charitable bequests generate tax receipts for your estate. The executor can claim tax credits for up to 100% of your net income in your final tax return. Unused credits can be applied to the previous year's return.

Tax benefit comparison:

Consider your tax situation when choosing between lifetime and testamentary giving. High-income earners may benefit more from spreading charitable deductions over several years through lifetime giving.

Mental Capacity Requirements Under Canadian Common Law And Provincial Legislation

Creating or changing a will requires testamentary capacity under Canadian law. You must understand the nature and effect of making a will.

You need to know what property you own and its approximate value. You also need to know who might reasonably expect to inherit from your estate.

The capacity requirement is lower for making a will than for other legal decisions. Complex charitable bequests may require higher understanding levels.

Signs of sufficient capacity:

- Understanding your assets and their value

- Knowing your potential beneficiaries

- Comprehending the effects of your will

- Making decisions free from undue influence

If you have concerns about future capacity, make your will sooner rather than later. Document your decision-making process with your lawyer to prevent future challenges.

Medical conditions like dementia can affect capacity. Regular capacity assessments may be necessary if cognitive decline is possible.

The Importance Of Canadian Professional Advice

Estate planning with charitable bequests involves complex legal and tax considerations. Professional advice ensures your will achieves your goals and complies with Canadian law.

Lawyers draft clear bequest language and ensure proper charity identification. They also structure gifts to minimize tax and avoid common legal problems.

Tax professionals can model different giving scenarios. They show how charitable bequests affect your estate's total tax bill and net value to heirs.

Professional team members:

- Estate planning lawyer for legal drafting

- Accountant for tax planning

- Financial planner for overall strategy

- Charity representatives for gift structuring

Get multiple opinions for large or complex charitable gifts. The cost of professional advice is small compared to potential problems from poorly planned bequests.

Choose professionals with specific experience in charitable giving and Canadian tax law. General practitioners may miss important opportunities or requirements.

Choosing Your Charitable Beneficiaries

Selecting the right charitable beneficiaries requires careful research and understanding of Canada's regulatory framework. Verify charity registration status, review financial transparency, and consider qualified donees beyond traditional charities.

Researching Canadian Charities And Qualified Donees

Before including any organization in your will, verify their status as a qualified donee under the Income Tax Act. Only gifts to qualified donees generate tax receipts for your estate.

The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) maintains strict criteria for charitable registration. Organizations must operate exclusively for charitable purposes: relief of poverty, advancement of education, advancement of religion, or other purposes benefiting the community.

Key research steps include:

- Confirming current registration status

- Reviewing the organization's mission and activities

- Checking financial statements and annual filings

- Verifying the correct legal name

Consider the charity's longevity and stability. Organizations that have operated successfully for many years may be more likely to continue their work long-term.

Using CRA's List of charities and other qualified donees

The CRA's online List of charities and other qualified donees is our main verification tool. We can search by charity name, registration number, or location to confirm an organization's status.

The database provides essential information, including:

- Current registration status

- Business number (BN) with registration number

- Date of registration

- Designated gifts status

- Contact information

Active status means the charity is currently registered and can issue tax receipts. Revoked status means the organization cannot operate as a charity or issue receipts.

We must use the exact legal name shown in the database when drafting our will. Informal names or abbreviations may delay or complicate matters for our executor.

Understanding CRA Registration Numbers

Every registered charity receives a unique nine-digit registration number with their Business number (BN) with registration number. This 15-digit combination serves as the official identifier.

The registration number format is 123456789RR0001. "RR" shows registered charity status, and the last four digits identify different programs within larger organizations.

Important considerations:

- Always verify the complete 15-digit number

- National charities may have separate registration numbers for different branches

- Some organizations operate multiple registered charities under one umbrella

We should include both the charity's legal name and registration number in our will to ensure proper identification.

Reviewing T3010 Filings For Financial Transparency

Registered charities file annual T3010 returns that detail their finances and activities. These public documents help us evaluate how organizations use donations.

Key financial metrics to examine:

- Fundraising ratio: Administrative and fundraising costs versus program spending

- Revenue sources: Government funding, donations, investment income

- Expenditure breakdown: Program delivery versus overhead costs

- Asset management: Reserves and long-term sustainability

Most effective charities spend 70-80% of their budget on programs rather than administration. Newer charities or those building infrastructure may spend differently.

We can access T3010 filings through the CRA database or request copies from organizations.

Checking Compliance History And Revocations

The CRA monitors charities for compliance with federal regulations. We should check for any compliance issues or sanctions before making bequest commitments.

Red flags include:

- Recent suspension of receipting privileges

- Outstanding compliance requirements

- History of late filing penalties

- Previous revocation and re-registration

The List of charities and other qualified donees shows current status but may not detail historical issues. We can contact the CRA for compliance history or review the organization's annual filings for disclosed penalties.

Charities with clean compliance records show better governance and lower risk of future problems affecting our gift.

Evaluating Governance Under Canadian Charity Law

Strong governance shows an organization's ability to manage funds and continue operations long-term. We should assess leadership structure and decision-making processes.

Governance indicators include:

- Independent board of directors

- Clear conflict of interest policies

- Regular board meetings and oversight

- Transparent reporting practices

- Succession planning

Well-governed charities publish annual reports beyond their required T3010 filings. These reports often include board member information, strategic plans, and detailed program outcomes.

We may request governance documents from organizations or review their websites for transparency indicators.

Qualified Donees Beyond Registered Charities

Canadian tax law recognizes several categories of qualified donees besides registered charities. These organizations can also issue tax receipts for estate gifts.

Qualified donee categories include:

- Registered Canadian amateur athletic associations

- Registered journalism organizations

- Canadian municipalities

- Federal, provincial, and territorial governments

- Certain foreign charities

- United Nations agencies

Each category has specific requirements and limitations. We must verify qualification status through government databases or directly with the CRA.

Some qualified donees may have restrictions on gift types or purposes that affect estate planning.

Registered Canadian Amateur Athletic Associations (RCAAAs)

RCAAAs promote amateur athletics in Canada and qualify for charitable tax treatment. They must register with the CRA and meet specific operational requirements.

RCAAA requirements include:

- Exclusive focus on amateur sport

- Canadian organization and control

- No professional sport activities

- Regular filing of annual information returns

We can verify RCAAA status through the CRA database. These organizations receive similar registration numbers with "RR" designation.

RCAAAs may operate locally, provincially, or nationally. We should confirm the organization matches our intended charitable impact.

Registered Journalism Organizations (RJOs)

RJOs are a newer category of qualified donee, created to support independent journalism in Canada. They must meet specific criteria for registration and maintenance.

RJO qualification requirements:

- Primary purpose of journalism in the public interest

- Canadian organization and control

- Independence from government and political parties

- Adherence to professional journalism standards

The CRA maintains a separate section in their database for RJOs. We should verify current status as this category faces ongoing regulatory development.

RJOs allow us to support media diversity and democratic discourse through estate giving.

Canadian Municipalities

All Canadian municipalities automatically qualify as donees without separate registration. We can make gifts to cities, towns, counties, or other municipal governments.

Municipal gift considerations:

- Gifts typically support specific municipal projects or general operations

- No registration number required

- May need to specify intended use or department

- Local governments may have gift acceptance policies

We should contact municipal offices to discuss estate gift procedures and any restrictions on gift types or purposes.

Municipal gifts often support parks, libraries, recreation facilities, or community programs.

Federal, Provincial, And Territorial Governments

All levels of Canadian government qualify.

Getting The Details Right: Canadian Legal Requirements

Proper identification of charitable recipients and precise legal language are essential for valid charitable bequests in Canada. The charitable registration status, correct legal names, and protective clauses determine if your intended gifts will reach their destinations and provide tax benefits.

Finding The Correct Legal Name

Every registered charity in Canada has an official legal name on their governing documents and CRA registration. This legal name may differ from the name they use in public or marketing materials.

We must use the charity's exact legal name in our will to ensure proper identification. For example, a charity might be known publicly as "Help Kids Read," but their legal name could be "The Children's Literacy Foundation of Ontario."

The legal name appears on the charity's letters patent, articles of incorporation, or other founding documents. We can also find it through the CRA's List of charities and other qualified donees by searching the registration number.

Using an incorrect name can delay or prevent the bequest from reaching the intended charity. Our executor may need to seek court approval to clarify our intentions, which costs time and money from our estate.

Why Operating Names And "Doing Business As" Names Aren't Sufficient

Many charities operate under trade names or "doing business as" names that are more descriptive than their legal names. These operating names have no legal standing for bequest purposes.

A charity might be legally incorporated as "The Society for Environmental Protection and Education" but operate as "Green Future Canada." Only the legal name creates a binding obligation in our will.

Operating names can change without notice or legal formality. Multiple organizations might use similar operating names, creating confusion about our intended recipient.

Provincial business registries may list operating names, but these don't establish the charity's legal identity. We need the name from incorporation documents or CRA registration records.

CRA Charities Listing: Account Name Vs. Legal Name

The CRA charity database shows both account names and legal names, but these may not always match. The account name is how CRA refers to the charity, while the legal name comes from incorporation documents.

We should cross-reference both names when researching our chosen charity. Sometimes the CRA account name includes abbreviations or slight variations from the legal name.

The registration number provides the most reliable identification method. Even if names change, the registration number stays the same throughout the charity's existence.

We can verify information by calling CRA's charities directorate or checking multiple sources. This extra step prevents costly mistakes in our will drafting.

Reviewing Letters Patent, Articles Of Incorporation, Or Governing Documents

Letters patent or articles of incorporation contain the charity's official legal name as registered with provincial or federal authorities. These documents provide the most authoritative source for proper identification.

We can request copies of these documents from the charity or obtain them through provincial corporate registries. Most provinces maintain online databases where we can search by organization name or number.

The governing documents also show the charity's stated purposes and powers. This information helps us understand whether our intended gift aligns with their legal mandate.

Changes to legal names require formal amendment processes that create paper trails. We can track name changes through updated articles or supplementary letters patent.

Provincial Vs. Federal Incorporation Considerations

Charities can incorporate provincially or federally, which affects where we find their legal documentation. Federally incorporated charities register with Corporations Canada, while provincial charities register with their home province.

Federal incorporation allows operation across Canada but doesn't automatically grant charitable status. The charity must still register separately with CRA for tax purposes.

Provincial incorporation limits operations to that province unless the charity registers extra-provincially elsewhere. The legal name reflects the incorporating jurisdiction's requirements and language laws.

We need to check the correct registry based on the charity's incorporation type. The CRA database shows whether incorporation was federal or provincial.

Drafting Precise Bequest Language For Canadian Wills

Precise language removes ambiguity about our charitable intentions and reduces the risk of failed bequests. Our will clause should include the charity's full legal name, registration number, and current address.

A well-drafted charitable bequest clause reads: "I give [$amount/percentage/description of property] to [Full Legal Name of Charity], a registered charity located at [address], bearing registration number [CRA registration number]."

We should specify whether the gift is a general bequest (unrestricted use), specific bequest (particular purpose), or contingent bequest (conditional on certain circumstances).

The clause should state what happens if the charity cannot accept the gift or no longer exists when our estate is distributed.

Charitable Registration Status Clauses

Including charitable registration status language protects our estate's tax position and clarifies our intent to benefit only registered charities. This clause ensures our gift qualifies for charitable tax credits.

We can add: "provided that at the time of my death, the organization remains a registered charity under the Income Tax Act (Canada)." This condition protects against charities that lose their status.

The clause should specify what happens if the charity loses registration before our death. Options include redirecting the gift to another charity or returning it to the estate.

This language helps our executor avoid making gifts that don't qualify for tax benefits or that we wouldn't have intended.

What Happens If A Charity Loses CRA Registration?

When a charity loses CRA registration, it cannot issue tax receipts or legally operate as a charity. Our bequest to such an organization may fail or lose its tax benefits.

CRA revokes registration for reasons like failure to file returns, operating outside charitable purposes, or inadequate governance. The charity can appeal, but the process can take years.

If we don't include protective language, our executor might still need to make the gift. However, our estate loses the charitable tax credit, which could increase the tax burden on other beneficiaries.

Our will should address this scenario by naming alternative charities or directing that failed charitable gifts return to our estate.

Including Protective Language

Protective clauses help safeguard your charitable intentions if circumstances change between will signing and estate distribution.

These provisions guide your executor in handling unexpected situations.

Key protective elements include naming alternative charities if your first choice cannot receive the gift.

They also provide directions for handling merged or renamed organizations and allow your executor to select similar charities if needed.

You might include this: "If the named charity has ceased to exist or is no longer a registered charity, my executor may direct this gift to a similar registered charity serving comparable purposes."

This language avoids court applications and gives your executor reasonable discretion while honoring your charitable wishes.

Restricted Vs. Unrestricted Gifts Under Canadian Charity Law

Unrestricted gifts let charities use your donation for any purpose within their mandate.

These gifts provide maximum flexibility and are generally preferred by charities.

Provincial Considerations: How Your Location Matters

Each province and territory in Canada has its own rules for wills and estates.

These differences affect how charitable bequests work and what steps your estate must follow.

Provincial Variations In Estate Law

Estate law varies significantly across Canada.

Each jurisdiction has its own approach to handling wills and charitable gifts.

Common law provinces follow similar principles but have different specific rules.

All provinces except Quebec use common law, but details like witness requirements and executor duties change from place to place.

Statutory differences create practical challenges.

Some provinces require two witnesses for wills, while others have different age requirements or waiting periods before probate.

Charitable bequest recognition follows different timelines across provinces.

Your estate may need to wait longer in some provinces before the charity receives official donation receipt for income tax purposes, which affects when tax benefits become available.

Wills And Estates Legislation By Province/Territory

Each province has specific laws governing wills and estates:

Key differences include formal requirements for valid wills.

Some provinces allow more flexibility in how you can change or revoke charitable bequests.

Age requirements vary slightly.

Most provinces set the minimum age at 18, but some allow younger people to make wills in certain cases.

Probate Fees And Estate Administration Tax

Probate costs differ between provinces.

These fees directly impact how much your charity receives from your bequest.

Ontario charges estate administration tax on a sliding scale.

Estates under $50,000 pay $5 per $1,000, while larger estates pay $15 per $1,000 on amounts over $50,000.

British Columbia has probate fees of $6 per $1,000 for the first $25,000.

Amounts between $25,000 and $50,000 pay $14 per $1,000, and estates over $50,000 pay $14 per $1,000 on the total value.

Alberta eliminated probate fees in 2020.

This makes Alberta one of the most cost-effective provinces for estate administration.

Quebec has much lower costs because it uses a different legal system.

Notarial wills often avoid probate entirely.

Intestacy Rules If No Valid Will Exists

If someone dies without a valid will, provincial intestacy laws decide who gets the assets.

These rules rarely include charitable gifts.

Spouse and children usually receive priority under intestacy rules.

The exact division depends on your province and family situation.

No automatic charitable giving happens under intestacy.

Your intended charitable bequest will not occur unless you document it in a valid will.

Provincial variations in intestacy can be substantial.

Ontario gives different amounts to surviving spouses than British Columbia or Alberta.

Asset distribution timelines also vary.

Some provinces require longer waiting periods before distributing assets to heirs.

Quebec's Unique Civil Law System

Quebec uses civil law instead of common law.

This creates significant differences for charitable bequests and estate planning.

Civil Code of Quebec governs all estate matters.

The rules and procedures differ from other Canadian provinces.

Forced heirship concepts do not exist in Quebec, but family members have stronger rights to contest wills.

This can affect charitable bequests if family members object.

Three types of wills are recognized: notarial, holograph, and witnessed wills.

Each has different requirements and probate processes.

Language requirements may apply in Quebec.

Wills written in English might need translation during probate proceedings.

Notarial Wills Vs. Holograph Wills

Different provinces accept different types of wills, which affects how you document charitable bequests.

Notarial wills are only available in Quebec.

A notary prepares these wills with specific legal formalities, and they rarely require probate.

Holograph wills are handwritten and signed by you.

Most provinces accept these, but they must meet strict requirements and be entirely in your handwriting.

Witnessed wills are the most common type across Canada.

Two witnesses must sign in your presence and in each other's presence.

Charitable bequest language must be clear in any will type.

Vague descriptions can cause problems for executors and charities.

Different Terminology And Requirements

Provincial legislation uses different terms for the same concepts.

Understanding local terminology helps ensure your charitable bequest works properly.

Executor vs. Estate Trustee: Ontario uses "estate trustee" while most other provinces use "executor."

The role remains the same.

Probate vs. Grant of Probate: Different provinces use different terms for court approval of wills.

The process achieves the same legal objectives.

Witness requirements vary in important ways.

Some provinces require witnesses to know the document is a will, while others only require they witness your signature.

Revocation rules differ between provinces.

The methods for cancelling or changing charitable bequests follow different procedures.

Provincial Executor Compensation Guidelines

Executor compensation affects how much money remains for your charitable bequest.

Each province has its own approach to executor fees.

Percentage-based fees are common in Western provinces.

Executors usually receive 2-5% of the estate value, depending on complexity and provincial guidelines.

Ontario allows "care and management" fees plus a percentage for distribution.

The total often reaches 2-3% of estate value for straightforward estates.

Quebec sets lower fee guidelines.

Executors (called liquidators) typically receive 1-2% of estate value.

Family executors often waive fees, leaving more money for charitable bequests.

Professional executors rarely waive compensation.

Where To Probate: Provincial Superior Courts

Probate applications must be filed in the correct provincial court.

This determines which rules apply to your charitable bequest.

Superior Courts in each province handle probate applications.

The specific court names vary, but the function remains the same.

Jurisdiction rules usually require probate where the deceased lived at death.

If you own property in multiple provinces, you may need to file in more than one court.

Common Pitfalls Under Canadian Law

Life events, asset ownership structures, and beneficiary designations can affect your charitable bequest plans.

Provincial laws can create automatic revocations and tax consequences that many Canadians do not expect.

Life Events That Affect Your Canadian Will

Major life changes can invalidate your will without warning.

Canadian provinces have strict rules about when wills become void.

These laws exist to protect spouses and families, but they can also cancel your charitable bequests.

Marriage automatically revokes most wills in Canada.

Only Prince Edward Island allows married people to keep their old wills.

All other provinces require a new will after marriage.

Your charitable gifts disappear when your will becomes invalid.

The province's intestacy laws take over instead.

Having children doesn't revoke your will.

But it can reduce what goes to charity, as some provinces give children automatic rights to your estate.

Adoption creates the same legal relationship as biological children.

Adopted children get the same inheritance rights under provincial law.

Marriage And Remarriage: Automatic Revocation In Most Provinces

Getting married wipes out your existing will in most provinces.

This rule catches many Canadians off guard.

The revocation happens automatically on your wedding day.

You do not need to do anything; the law makes your will void.

British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon all follow this rule.

Only Prince Edward Island lets you keep your old will after marriage.

Even then, your spouse gets legal rights that might reduce charitable bequests.

Common-law relationships do not trigger automatic revocation, but they can still affect how your estate is divided.

Remarriage after divorce creates the same problem.

Your second marriage voids any will you made after your first marriage ended.

Divorce: Partial Revocation Rules Vary By Province

Divorce does not cancel your entire will like marriage does.

Instead, it removes your ex-spouse from the document.

Most provinces treat divorced spouses as if they died before you.

Any gifts to your ex-spouse go to the backup beneficiaries.

This can accidentally increase your charitable bequests or reduce them if your ex-spouse was supposed to get assets that would later go to charity.

Ontario has special rules about divorced spouses and wills.

The Family Law Act gives divorced spouses some continued rights in certain situations.

Quebec follows civil law, not common law.

Divorce affects wills differently there, so you need Quebec legal advice for accurate information.

Some provinces void appointments of ex-spouses as executors.

Others let the appointment stand unless you change it.

The Importance Of "In Contemplation Of Marriage" Clauses

You can protect your will from marriage revocation with special wording.

This clause tells the court you planned to marry when you signed your will.

The clause must name your future spouse specifically.

General language like "my future husband" will not work in most provinces.

"I make this will in contemplation of my marriage to [full legal name]" is the standard format.

Some provinces require additional specific language.

This protection only works if you actually marry the person you named.

Marrying someone else still revokes your will.

The clause protects your entire will, including charitable bequests.

Without it, you need to make a new will after your wedding.

Not all provinces recognize contemplation of marriage clauses equally.

Check your provincial law before relying on this protection.

Regular Will Reviews

Life changes can happen gradually or suddenly. Regular reviews catch problems before they affect your charitable plans.

We recommend reviewing your will every three to five years. Major life events should trigger immediate reviews.

New grandchildren, deaths in the family, and changes in your financial situation all matter. Changes to the charities you want to support also matter.

Charities can merge, close, or lose their registration. Your bequest might fail if the organization doesn't exist when you die.

Tax laws change over time. What worked for charitable giving five years ago might not be optimal today.

Keep a list of your will's key provisions. This makes it easier to spot problems during reviews.

Asset Ownership Issues In Canada

How you own assets affects whether they're part of your estate. Many Canadians accidentally exclude assets from their charitable bequests.

Assets that pass by right of survivorship bypass your will entirely. Joint bank accounts and jointly owned real estate work this way.

This reduces your estate's value. Smaller estates mean smaller charitable bequests if you're giving a percentage.

Different ownership structures have different tax consequences. Some trigger immediate capital gains. Others defer taxes until later.

Understanding these structures helps you plan better charitable gifts. You can avoid accidentally excluding assets you meant to include.

Joint Tenancy With Right Of Survivorship

Joint tenancy means all owners have equal rights to the entire property. When one owner dies, the others automatically get their share.

The deceased owner's share doesn't go through their estate. It passes directly to the surviving joint tenants.

This can exclude your house, cottage, or investments from charitable bequests. The assets aren't available for your will to distribute.

Joint tenancy works well for spouses who want everything to go to each other first. It's problematic if you want some assets available for charity.

Adding adult children as joint tenants can trigger immediate tax consequences. Canada Revenue Agency might treat this as a gift.

Consider tenancy in common instead if you want more control over how assets pass at death.

Tenancy In Common

Tenants in common own specific percentages of property. Each owner can sell their share or leave it in their will.

Your percentage goes through your estate when you die. This makes it available for charitable bequests.

The percentages don't have to be equal. You might own 60% while your spouse owns 40%.

This structure gives you more control over charitable planning. But it can complicate things for surviving owners.

Your heirs become co-owners with your spouse or other surviving tenants. This can create family conflicts.

Tenancy in common property still needs to go through probate. Factor probate fees into your planning.

The Pecore Presumption And Resulting Trusts

Canadian courts apply special rules when parents transfer assets to adult children. The Pecore presumption affects how these transfers work.

Adding adult children to bank accounts or property titles creates a legal presumption. Courts assume the child holds the asset for the parent's benefit.

This means the asset returns to your estate when you die.

Tax Optimization Strategies For Canadians

Canadian taxpayers can maximize charitable giving through strategic tax planning. Donation tax credits, income limits, and timing all matter.

Key strategies include understanding how credits work at death, managing income thresholds, and exploring alternatives like securities donations and RRSP/RRIF gifts.

Understanding How Donation Tax Credits Work At Death

When you make charitable bequests, the donation tax credit works differently than during your lifetime. The estate receives a charitable donation receipt for your final tax return.

You can also use the receipt on the tax return for the year before death. This gives you more flexibility to maximize the tax benefit.

The executor decides how to split the donation between these two years. They should choose the option that provides the greatest tax savings.

Federal Credit: 15% (First $200) + 33% (Amounts Over $200)

The federal donation tax credit starts at 15% for the first $200 you donate each year. For amounts over $200, you get a 33% credit rate (29% for gifts claimed before 2024).

This means a $1,000 donation gives you a federal credit of $294. Calculate this as ($200 × 15%) + ($800 × 33%) = $30 + $264 = $294.

For large charitable bequests, most of the donation receives the higher 33% rate. Bigger gifts become more tax-efficient than smaller ones.

Provincial Credits: Varies By Province

Each province sets its own donation tax credit rates. These rates vary significantly across Canada.

Provincial credit rates for donations over $200:

- Ontario: 11.16%

- British Columbia: 14.7%

- Alberta: 10%

- Quebec: 25.75%

- Nova Scotia: 16.67%

When you combine federal and provincial credits, your total can reach 44% to 54% depending on where you live. Charitable giving becomes a powerful tax strategy.

The 100% Of Net Income Limit In Year Of Death And Preceding Year

During your lifetime, you can claim donations up to 75% of your net income each year. At death, this limit increases to 100% of net income.

You can use this 100% limit for both the year of death and the preceding year. This gives your estate more room to claim large charitable bequests.

If your bequest exceeds these limits, you can carry forward unused amounts for up to five years. However, this carry-forward happens after death and may create complications.

The Problem Of Insufficient Taxable Income At Death

Many Canadians face a common problem at death. Your charitable bequest may be larger than your taxable income, limiting the tax benefit.

If you have low income in your final years, you cannot fully use large donation receipts. The excess donations get carried forward but may never provide tax savings.

This situation is especially common for retirees with modest pension income. Planning ahead helps avoid this tax trap.

Deemed Disposition Triggering Capital Gains

At death, Canadian tax law treats you as selling all your assets. This "deemed disposition" can create large capital gains on your final tax return.

These capital gains increase your taxable income in the year of death. Higher income gives you more room to claim charitable donation receipts.

You can use this situation strategically. Large charitable bequests can offset the tax from deemed disposition and reduce the overall tax burden on your estate.

When Estates Can't Fully Utilize Donation Receipts

Sometimes your estate cannot use all the donation receipts, even with the enhanced limits at death. This wastes valuable tax credits.

Common situations include:

- Low lifetime income with large bequests

- Insufficient capital gains at death

- Poor timing of the charitable gift

When this happens, your estate loses the tax benefit permanently. The unused credits cannot help your beneficiaries or the estate.

Strategic Lifetime Giving Approaches

Making charitable gifts during your lifetime often provides better tax results than bequests. You can control the timing and maximize your tax brackets.

Spread large donations over several years to stay within the 75% income limit. This approach uses your donation receipts more efficiently.

Benefits of lifetime giving:

- Better control over tax timing

- Ability to see the impact of your gifts

- More flexibility in tax planning

- Guaranteed use of tax credits

Consider making regular donations instead of one large bequest.

Using The Donation Carry-Forward

You can carry forward unused donation amounts for up to five years. This rule helps when your donations exceed the annual income limits.

The carry-forward works during your lifetime and continues after death. Your estate can use carried-forward amounts from previous years.

Strategic timing helps maximize this benefit. You might make a large donation in a high-income year and carry forward the excess.

Income Splitting Opportunities With Family

Spouses can share donation receipts to optimize their combined tax savings. Claim donations against the higher-income spouse's return.

This strategy works because the higher earner likely pays taxes at a higher rate. The donation tax credit provides greater savings when applied to higher-income tax returns.

You can also time donations to coincide with years when one spouse has unusually high income. This maximizes the tax benefit for your family.

Donating Appreciated Securities

Donating publicly traded securities directly to charity eliminates capital gains tax. This strategy provides double tax benefits.

Example: You own stock worth $10,000 that cost $4,000. If you sell and donate cash, you pay tax on $6,000 in capital gains. If you donate the stock directly, you avoid this tax entirely.

You still receive a donation receipt for the full $10,000 value. This approach works well for long-held investments with large gains.

Donating RRSP/RRIF Assets Directly To Charity

You can name a charity as the beneficiary of your RRSP or RRIF. The charity receives the funds directly, and your estate gets a donation receipt.

This strategy helps offset the income tax from RRSP/RRIF withdrawals at death. These registered accounts become fully taxable when you die.

Tax benefits:

- Estate receives charitable donation receipt

- Receipt can offset RRSP/RRIF income inclusion

- Reduces overall tax burden on the estate

This approach works well for large registered account balances.

Gifts Of Ecologically Sensitive Land

Donating certified ecological property provides enhanced tax benefits. You can claim up to 100% of your net income for these gifts, even during your lifetime.

The property must be certified as ecologically sensitive by Environment and Climate Change Canada. The certification process takes time and requires professional help.

Working With Canadian Estate Planning Professionals

Successful charitable bequest planning requires working with qualified professionals. The right team includes specialized lawyers, executors who understand their duties, and tax advisors familiar with charitable giving rules.

Finding A Qualified Wills And Estates Lawyer

You need a lawyer who specializes in estate planning and charitable giving. General practice lawyers may not know the complex rules around charitable bequests.

Look for lawyers who work regularly with charitable organizations. They know how to structure bequests to maximize tax benefits while avoiding common problems.

Key qualifications to seek:

- Active membership in provincial law society

- Focus on wills and estates (not just occasional work)

- Experience with charitable bequests specifically

- Knowledge of both provincial estate law and federal tax rules

Ask potential lawyers about their recent charitable bequest cases. How many have they handled in the past year? What types of charities were involved?

Provincial Law Society Directories

Each province maintains an online directory of licensed lawyers. These directories let you search by location and practice area.

Major provincial law societies:

- Ontario: Law Society of Ontario (LSO)

- British Columbia: Law Society of British Columbia

- Alberta: Law Society of Alberta

- Quebec: Barreau du Québec

The directories show lawyer credentials, practice areas, and disciplinary history. You can filter results to find lawyers who list "wills and estates" or "charitable planning" as specialties.

Most directories include lawyer contact information and firm details. Some show years of practice and professional certifications.

Specialization Certifications

Several provinces offer formal certification programs for estate planning lawyers. These certifications require extra training and ongoing education.

Ontario offers certification through the Law Society's specialist program. Certified specialists prove their expertise through peer review and continuing education.

British Columbia provides similar specialist recognition for estate lawyers. The certification process includes written exams and practice requirements.

Look for lawyers with these formal certifications. They show advanced knowledge beyond basic legal training.

Some lawyers also hold designations from groups like the Canadian Association of Gift Planners (CAGP). These designations show a commitment to staying current with charitable giving practices.

Questions To Ask

Before hiring an estate lawyer, ask specific questions about their experience with charitable bequests.

Essential questions include:

- How many charitable bequests have you drafted in the past two years?

- What types of charitable gifts do you recommend most often?

- How do you handle specific vs. residual bequests?

- What's your fee structure for will preparation?

Ask about their relationships with local charities. Do they work with planned giving officers? How do they verify charity registration status?

Find out how they approach tax planning. Ask how they structure bequests to maximize tax credits for the estate.

Request references from recent clients who made charitable bequests. A qualified lawyer should provide references with client permission.

The Role Of Your Executor/Estate Trustee

The executor (called estate trustee in Ontario) has legal duties when handling charitable bequests. They must follow the will's instructions and meet all legal requirements.

Key executor responsibilities:

- Obtain charity registration numbers

- Verify charities are still operating

- Calculate exact bequest amounts

- Obtain proper tax receipts

- File estate tax returns correctly

Discuss charitable bequests with your chosen executor before finalizing the will. They need to understand the extra work involved.

Some executors may not feel comfortable handling complex charitable gifts. Consider appointing a professional executor or trust company for estates with significant charitable components.

The executor is personally liable for mistakes in handling bequests. Beneficiaries or charities can sue if the executor fails to fulfill their duties.

Legal Obligations Under Provincial Law

Provincial laws govern how executors handle charitable bequests. These laws vary across Canada but share common requirements.

Universal obligations include:

- Following exact will instructions

- Obtaining court approval for major decisions

- Keeping detailed records of all transactions

- Providing accountings to beneficiaries

Ontario's Trustee Act requires executors to invest estate funds prudently while settling bequests. They must not delay charitable distributions without good reason.

British Columbia has similar requirements under the Wills, Estates and Succession Act. Executors must distribute charitable bequests within reasonable timeframes.

Most provinces allow courts to modify charitable bequests if the original charity no longer exists. Courts direct funds to similar charitable purposes.

Compensation Guidelines By Province

Executor compensation varies by province and estate complexity. Charitable bequests can increase the work required and justify higher fees.

Typical compensation ranges:

- Ontario: 2.5% of estate value plus care and management fees

- British Columbia: Up to 5% of gross estate value

- Alberta: "Fair and reasonable" compensation based on work performed

Professional executors often charge hourly rates instead of percentage fees. Rates usually range from $200 to $500 per hour depending on complexity and location.

Discuss compensation expectations with potential executors upfront. Some family members may waive fees, but professionals will always charge.

Complex charitable bequests involving multiple charities or ongoing trusts require more work. Agree on higher compensation in advance if needed.

Should You Appoint The Charity As Executor?

Large charities sometimes serve as executors for estates making substantial bequests. This arrangement has both advantages and risks.

Benefits of charity executors:

- Deep knowledge of charitable tax rules

- Professional estate administration

- No conflicts between charitable and family interests

- Permanent institution (won't die or become unavailable)

Potential drawbacks:

- May prioritize charity interests over family

- Professional fees can be high

- Less personal relationship with family

- May lack knowledge of specific assets or family dynamics

Only consider charity executors for estates where charitable bequests make up a major portion of total assets. For smaller gifts, family or professional executors usually work better.

Engaging Canadian Tax Advisors

Charitable bequests create complex tax situations. You need tax advisors who understand both estate taxation and charitable giving rules.

Look for Chartered Professional Accountants (CPAs) with estate and trust experience. They should know how charitable donations affect terminal tax returns and estate distributions.

Key tax considerations include:

- Timing of charitable donation claims

- Capital gains elimination on gifted securities

- Interaction with other estate deductions

- Provincial tax credit differences

Some tax advisors specialize in charitable sector work. They understand charity operations and can structure gifts for maximum benefit.

Engage tax advisors early in the planning process. Early advice can help you develop effective strategies.

Protecting Your Will Under Canadian Law

Canadian law requires specific steps to make your will legally valid and protect it from challenges. Each province has different rules for signing, witnessing, and storing wills that affect charitable bequests.

Proper Execution Requirements

A valid will in Canada must meet strict legal requirements that vary by province. These requirements protect both the testator and beneficiaries, including charities.

Key execution elements include:

- Legal age of majority in your province

- Sound mental capacity when signing

- Proper witnessing procedures

- Clear testator signature

- Written document format

Failure to meet these requirements can invalidate your entire will. Your charitable bequests may not reach their intended recipients.

Work with a qualified lawyer to ensure proper execution. Lawyers understand provincial variations and can prevent costly mistakes.

Common Law Provinces: Two Witnesses, Testator Signature

All provinces except Quebec follow common law will requirements. You must sign your will in the presence of two independent witnesses who are at least 18 years old.

Both witnesses must:

- Be present when you sign

- Sign the will themselves

- Not be beneficiaries or spouses of beneficiaries

- Have mental capacity to understand what they're witnessing

Important witness restrictions:

- Charity employees cannot witness if that charity receives a bequest

- Family members should not witness

- Lawyers preparing the will can witness

Witnesses do not need to read your will or know its contents. They only confirm your identity and that you signed willingly.

Quebec: Notarial, Holograph, Or Witnessed Wills

Quebec recognizes three types of valid wills under the Civil Code. Each type has different requirements and protection levels.

Notarial wills offer the strongest protection. A notary prepares and keeps the original document. Two witnesses must be present during signing.

These wills rarely face successful challenges.

Holograph wills must be entirely handwritten and signed by you. No witnesses are required, but these wills are more vulnerable to disputes about authenticity or mental capacity.

Witnessed wills follow rules similar to common law provinces. You sign before two witnesses who also sign the document.

Choose notarial wills for substantial charitable bequests. The extra cost provides significant protection against legal challenges.

Age Of Majority Requirements By Province

You must reach the age of majority in your province to make a valid will. This requirement affects when you can include charitable bequests in your estate planning.

Married minors can make valid wills in most provinces regardless of age. Military personnel may also have special provisions for earlier will-making.

If you made a will before reaching majority age, it becomes invalid. Create a new will after your 18th or 19th birthday to include charitable bequests.

Storage Options

Proper storage protects your will from loss, damage, or tampering. The location you choose affects how quickly your executor can access the document after your death.

Consider these factors when choosing storage:

- Security from theft or damage

- Accessibility for your executor

- Cost of storage services

- Climate control for document preservation

Never store your only copy in a safety deposit box. Bank policies may prevent immediate access after death, delaying charitable distributions.

Keep your will in a fireproof, waterproof location. Inform your executor and family members where to find it.

Lawyer's Vault

Most law firms offer secure document storage services. This option provides professional-grade security and easy access for your executor.

Advantages include:

- Fireproof and waterproof storage

- Professional oversight

- Direct contact with your executor

- Legal advice readily available

Your lawyer maintains detailed records of document location and access procedures. They can guide your executor through the probate process efficiently.

Annual storage fees typically range from $25 to $100. Many lawyers store wills at no charge for existing clients.

Ask about storage policies when preparing your will.

Court Registries

Several provinces allow will registration with court registries. This service creates an official record of your will's existence and location.

Provinces offering will registries:

- British Columbia

- Alberta

- Saskatchewan

- Nova Scotia

Registration fees range from $15 to $50. The registry doesn't store your actual will but maintains location information for executors.

This system helps prevent lost wills and ensures proper legal procedures. Official registration provides better protection for your charitable beneficiaries.

Home Storage Risks

Storing your will at home creates significant risks for charitable bequests. Family disputes, natural disasters, or simple misplacement can eliminate years of estate planning.

Common home storage problems:

- Fire or flood damage

- Accidental disposal by family members

- Tampering or destruction by disgruntled heirs

- Inability to locate the document

Home storage may seem convenient and cost-effective, but the risks often outweigh these benefits for substantial charitable gifts.

If you choose home storage, use a fireproof safe or filing cabinet. Tell multiple trusted people about the location and access methods.

Who Should Have Copies?

Strategic copy distribution helps your will reach the right authorities. It also maintains confidentiality during your lifetime.

Essential copy holders:

- Your primary executor

- Your lawyer

- One trusted family member or friend

Give copies, not originals, to most people. Courts need originals for probate proceedings.

Don't give copies to all beneficiaries, including charities. This prevents premature expectations and potential family conflicts.

Update all copy holders when you revise your will. Outdated versions can cause confusion and delay charitable distributions.

Digital Estates And Online Assets

Modern estates often include digital assets. These require special planning.

Digital assets can impact charitable bequests if not properly addressed.

Common digital assets:

- Online banking and investment accounts

- Digital currencies and wallets

- Social media accounts

- Cloud storage services

- Email accounts containing important documents

Create a separate digital asset inventory with access credentials. Store this information securely and update it regularly.

Many online platforms have specific policies for deceased users. Research these policies for accounts holding significant value.

Consider naming a digital executor with technical expertise. This person can work with your primary executor to locate and transfer digital assets to charitable beneficiaries.

Testamentary Capacity Challenges: Avoiding Will

Communicating Your Canadian Legacy

Sharing your charitable intentions requires balancing privacy and practical needs. These choices affect tax benefits, family relationships, and your charitable impact across Canada.

Should You Inform The Charity In Advance?

Informing charities about your planned bequest offers significant advantages. This approach is recommended for most donors, though it remains a personal choice.

Benefits of advance notification include:

- Ensuring the charity accepts your specific type of gift

- Confirming your bequest aligns with their current mission

- Receiving recognition during your lifetime if desired

- Building stronger relationships with the organization

Some charities cannot accept certain gifts. Real estate donations may be declined due to environmental concerns.

Complex or burdensome bequests might be refused if the charity lacks resources to manage them. Early communication prevents disappointment.

Your estate executor won't need to find an alternative beneficiary if your chosen charity declines the gift.

Confidentiality remains an option. You can inform the charity without disclosing specific amounts. This allows for planning discussions while maintaining privacy about your estate's value.

Benefits Of Legacy Society Membership

Many Canadian charities offer legacy societies for donors who include them in their wills. These groups provide valuable benefits beyond simple recognition.

Typical legacy society benefits include:

- Special events and behind-the-scenes access

- Regular updates on organizational impact

- Estate planning seminars and resources

- Priority invitations to major announcements

- Networking opportunities with like-minded donors

Legacy societies help charities plan for future funding. They can budget more effectively knowing committed supporters exist.

Membership often includes access to planned giving professionals. These experts can answer questions about optimal gift structures and tax implications in your province.

Some societies offer family benefits. Your children or grandchildren might receive scholarships, mentorship opportunities, or volunteer positions through these connections.

Privacy protection remains paramount. Most legacy societies allow anonymous participation if you prefer confidentiality while still accessing member benefits.

Confidential Vs. Public Recognition

Recognition preferences vary among Canadian donors. Both confidential and public approaches to charitable bequests have valid reasons.

Confidential bequests offer several advantages:

- Complete privacy for your family

- No pressure from other organizations

- Protection from increased solicitations

- Flexibility to change plans without explanation

Public recognition can inspire others to give. Your visible commitment might encourage friends, colleagues, or community members to consider similar gifts.

Anonymous options exist within public programs. Many charities list anonymous donors by gift size rather than name. This approach inspires others while protecting your privacy.

Consider your family's comfort level. Some relatives prefer private philanthropy, while others take pride in public recognition.

Professional advice helps balance these considerations. Estate lawyers can structure gifts to provide the right recognition while protecting your family's interests.

Discussing Plans With Family Members

Family conversations about charitable bequests require sensitivity and timing. Early discussions help prevent confusion and conflict after your death.

Key family members to include:

- Spouse or life partner

- Adult children who are potential heirs

- Primary beneficiaries of your estate

- Anyone serving as executor

Start with your values and motivations. Explain why specific causes matter to you rather than focusing on dollar amounts.

Consider family financial security first. Relatives need assurance that charitable gifts won't compromise their reasonable expectations or needs.

Address concerns directly. Some family members worry about reduced inheritances. Others may question charity effectiveness or management.

Timing matters. These conversations work best during calm periods, not during family stress or health crises.

Document family discussions. Written records can help executors later if questions arise about your intentions.

Managing Expectations Under Canadian Family Law

Canadian family law provides protections for certain relatives that can override will provisions. Legal requirements must be considered when planning charitable bequests.

Each province has different dependant relief legislation. These laws allow courts to vary will provisions if adequate support wasn't provided for eligible dependants.

Common dependants include:

- Surviving spouses or common-law partners

- Minor children

- Adult disabled children

- Other dependants you supported financially

Courts balance charitable intentions against family obligations. They rarely eliminate charitable bequests but may reduce them to provide adequate family support.

Prevention strategies include:

- Providing reasonable support for all dependants

- Documenting your decision-making process

- Obtaining family acknowledgment of your plans

- Structuring gifts to preserve core family support

Legal advice is essential when family situations are complex. Blended families, estranged relationships, or significant wealth require careful planning to achieve your charitable goals and meet legal obligations.

Dependant Relief Claims And Provincial Variation Statutes

Provincial variation statutes create extra complexity for charitable estate planning in Canada. These laws differ between provinces in scope and application.

Ontario's Succession Law Reform Act allows dependants to apply for support from estates. Courts consider factors like the dependant's financial needs, their relationship with the deceased, and the estate's size.

British Columbia's Wills, Estates and Succession Act includes moral obligations to family members. Courts can vary wills when provisions seem inadequate for people the deceased should have supported.

Alberta and other provinces have similar but distinct legislation. Each province defines eligible dependants differently and uses varying criteria for court decisions.

Time limits apply to these claims. Most provinces allow six months to two years for dependant relief applications after probate is granted.

Risk mitigation strategies include:

- Understanding your province's specific legislation

- Providing adequate support for all potential claimants

- Creating detailed explanations for your decisions

- Considering insurance to fund both family and charitable goals

Creating A Memorandum Of Wishes

A memorandum of wishes gives non-binding guidance to your executor about your charitable intentions. This document complements your formal will with extra context and explanation.

Include specific details about:

- Why you chose particular charities

- How you want gifts used if possible

- Alternative charities if primary choices cannot accept

- Your values and philanthropic philosophy

- Family considerations that influenced your decisions

This document helps executors understand your priorities. It's especially valuable for residual bequests where exact amounts aren't predetermined.

Update memorandums regularly. Your philanthropic interests may change, and charity circumstances evolve over time.

Legal formality isn't required. Simple, clear language works better than complex legal terms for expressing your wishes and motivations.

Share copies with relevant parties. Your executor, major beneficiary charities, and key family members should receive copies to understand your intentions fully.

Leaving A Statement Of Philanthropic Values

A philanthropic values statement creates lasting meaning beyond the financial impact of your charitable bequests. This document explains

Special Situations In Canadian Estate Planning

Certain charitable bequests require specialized planning due to their complexity or unique tax implications. International donations and gifts of non-traditional assets can significantly affect your estate's tax position.

Large Estates And Alternative Minimum Tax Considerations

When your estate is large, the alternative minimum tax (AMT) becomes important in charitable planning. The AMT applies when tax preferences reduce regular income tax below the minimum threshold.

Charitable donations can trigger AMT calculations if they create large deductions compared to income. Your estate may need to pay the higher of regular tax or AMT.

Key AMT triggers include:

- Charitable donations exceeding 75% of net income

- Capital gains donations creating large deductions

- Multiple years of carry-forward donations claimed at once

We recommend timing charitable gifts carefully in large estates. Spreading donations across multiple tax years can minimize AMT exposure.

Professional tax planning is essential when estate values exceed $5 million. The interaction between charitable deductions and AMT requires careful analysis to optimize tax savings.

Charitable Remainder Trusts Under Canadian Law

Charitable remainder trusts let you provide income to beneficiaries while ensuring charities receive the remainder. These trusts offer unique tax advantages for high-net-worth individuals.

Under Canadian law, you receive an immediate charitable tax receipt for the present value of the remainder interest. The trust pays income to designated beneficiaries for a set period or their lifetime.

Trust structure benefits:

- Immediate charitable tax deduction

- Income stream for beneficiaries

- Reduced capital gains on donated assets

- Estate tax savings

The charitable remainder must be at least 10% of the initial trust value. Income payments cannot exceed 50% annually of the initial fair market value.

These trusts work well with appreciated securities or real estate. Professional administration ensures compliance with trust rules and tax requirements.

Gifts Of Real Property

Donating real property to charity requires special consideration due to valuation and tax issues. Environmental assessments and title issues can complicate these donations.

You must obtain professional appraisals for real property donations exceeding $1,000. The Canada Revenue Agency may challenge valuations that appear excessive.

Important considerations:

- Environmental liability assessments

- Capital gains implications

- Property tax responsibilities until transfer

- Zoning and land use restrictions

Consider donating a partial interest in property if a full donation isn't practical. You can donate a remainder interest while retaining life use of the property.

Some charities cannot accept real property due to management constraints. Verify the charity's ability to receive and manage real estate before making commitments.

Gifts Of Private Company Shares

Private company shares offer unique opportunities and challenges for charitable giving. These donations can provide significant tax advantages and support your preferred causes.

Professional valuation determines the fair market value, especially for minority interests or restricted shares. Discounts for lack of marketability often apply to private company interests.

Valuation factors include:

- Company financial performance

- Market conditions in the industry

- Restrictions on share transfer

- Minority versus controlling interests

Private company donations work well when the charity can sell shares to third parties or back to the company. Some charities prefer cash donations over illiquid securities.

Consider the timing of private company donations carefully. Share values can fluctuate, affecting both tax benefits and charitable impact.

Cultural Property Donations

Cultural property donations receive special treatment under Canadian tax law through the Cultural Property Export and Import Act.

These donations can eliminate capital gains entirely.

The Cultural Property Review Board must certify donations as culturally significant to Canada.

Approved donations qualify for enhanced tax benefits beyond regular charitable donations.

Certification requirements:

- Outstanding significance to Canadian heritage

- National importance in art, history, or science

- Donation to designated Canadian institutions

Certified cultural property donations can be claimed at 100% of fair market value with no capital gains.

The donation credit can offset income tax completely in the year of donation.

Museums, galleries, and archives must be designated institutions to receive cultural property.

The certification process takes several months and requires detailed documentation.

Supporting Specific Programs

Directing charitable bequests to specific programs requires careful legal drafting to ensure your intentions are followed.

General charitable purposes provide more flexibility than restricted donations.

Your will should clearly identify the specific program or purpose you wish to support.

Include provisions for alternative uses if the designated program is discontinued.

Drafting considerations:

- Clear program identification

- Alternative purpose provisions

- Sunset clauses for time-limited programs

- Charity's discretion for implementation