Canadian Charity International Operations: Global Compliance

One of the most frequent questions Canadian charities ask our charity lawyers when coming to us to register their charity or expand its charitable scope is whether they can support international causes and organizations. The answer is a resounding yes—and thousands of Canadian charities are already doing exactly that. However, the path to global impact requires understanding the legal framework that governs how Canadian charities can operate internationally.

The confusion often stems from the complexity of Canada's Income Tax Act and the Canada Revenue Agency's (CRA) requirements for charitable organizations. Many charity leaders assume that supporting international causes is either prohibited or requires navigating an impossibly complex bureaucratic maze. In reality, while there are important rules to follow, the framework is quite clear once you understand the two fundamental pathways available to Canadian charities.

The Legal Foundation: Two Pathways to Global Impact

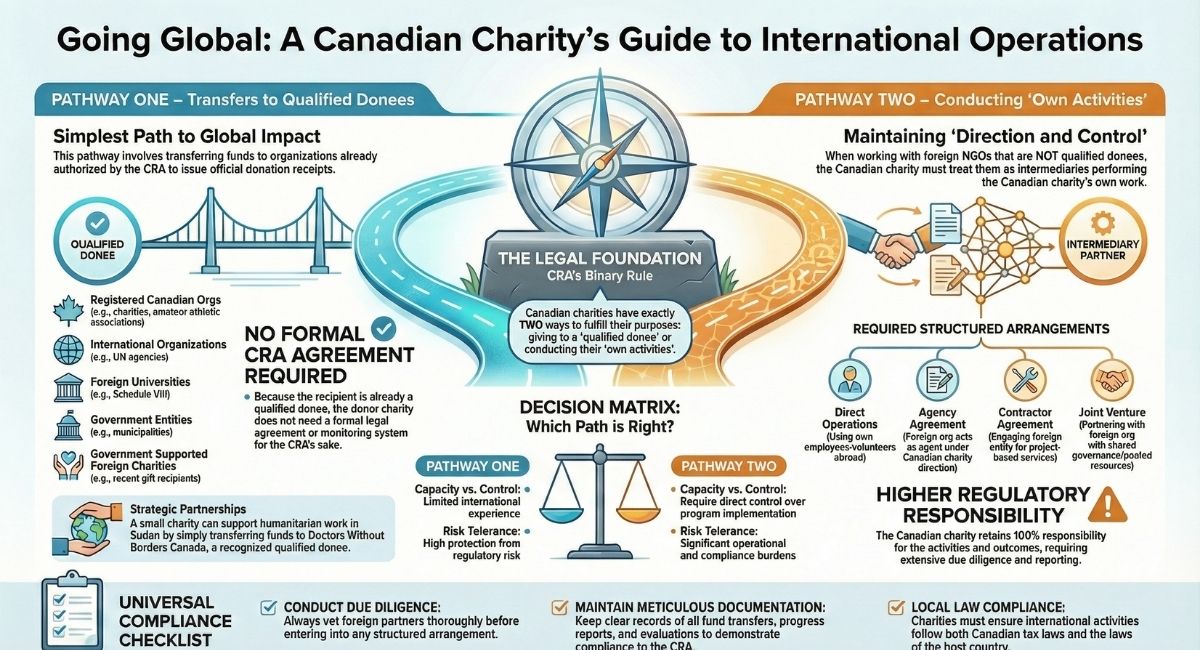

The Income Tax Act (Canada) provides Canadian charities with exactly two ways to fulfill their charitable purposes: they can either give money or assets to another "qualified donee," or they can conduct their "own activities" at home or abroad. There is no third option, and understanding this binary choice is crucial for any charity considering international work.

This framework applies not only to international operations but also to domestic activities. A Canadian charity cannot simply transfer funds to another Canadian organization that isn't a qualified donee, regardless of how worthy the cause might be. The CRA's approach is consistent: charitable funds must either go to qualified recipients or be used for the charity's own activities under proper oversight.

Pathway One: Transfers to Qualified Donees

The first and often simplest pathway for Canadian charities to support international causes is through transfers to qualified donees. These are organizations that can legally issue official donation receipts for gifts from individuals or corporations under the Income Tax Act.

Who Qualifies as a Qualified Donee?

The list of qualified donees is specifically defined in Canadian tax law and includes several categories relevant to international work:

Registered Canadian Organizations: This includes registered charities, registered Canadian amateur athletic associations, and registered national arts service organizations. These are often the most straightforward recipients for international funding, as they're already operating under CRA oversight.

Government Entities: Municipalities, municipal or public bodies performing government functions in Canada, and the governments of Canada, provinces, or territories all qualify. While these might seem less relevant for international work, they can sometimes be conduits for international aid programs.

International Organizations: The United Nations and its agencies represent a significant category for international charitable work. Canadian charities can transfer funds directly to UN organizations without complex agreements or monitoring requirements.

Foreign Universities: Universities outside Canada that have student bodies ordinarily including students from Canada are qualified donees, provided they appear on Schedule VIII of the Income Tax Regulations. This creates opportunities for educational and research partnerships.

Government-Supported Foreign Charities: Perhaps most importantly for international work, charitable organizations outside Canada become qualified donees if the Government of Canada has made a gift to them during the donor's taxation year or in the 12 months immediately before that period. This provision opens doors to supporting many international charitable organizations.

Housing Corporations: Housing corporations in Canada set up exclusively to provide low-cost housing for the aged represent another specialized category of qualified donee.

The Simplicity of Qualified Donee Transfers

The beauty of working with qualified donees lies in the simplicity of the arrangement. From the CRA's perspective, no formal agreement between the donor charity and the qualified donee is required. The transaction is straightforward: one qualified organization is supporting another qualified organization's charitable work.

Consider a practical example: A Canadian charitable organization with no experience in foreign operations wants to help people affected by humanitarian crises in Sudan. Rather than attempting to establish direct operations in a challenging international environment, they can support Doctors Without Borders Canada, a qualified donee with established expertise and infrastructure. The transfer is clean, simple, and legally sound.

However, while no agreement is required from a regulatory standpoint, donor charities often want to ensure their funds are used as intended. If the donor charity wishes to restrict the gift to specific purposes or geographic areas, they may choose to create a direction or agreement with the recipient organization. This isn't a CRA requirement but rather a practical governance measure.

The same principle applies to domestic examples. If a donor contributes to a community foundation with the request that their donation support AIDS work in sub-Saharan Africa, the foundation can transfer those funds to organizations like the Stephen Lewis Foundation or Canadian Crossroads International—both qualified donees—without needing formal agreements or monitoring from a regulatory perspective.

Strategic Advantages of the Qualified Donee Approach

For many Canadian charities, especially those without international experience, supporting qualified donees represents the safest and most efficient path to global impact. The donor charity benefits from the recipient organization's expertise, established relationships, and operational infrastructure while avoiding the complexity of direct international operations.

This approach also provides excellent protection from regulatory risk. Since both organizations are already under CRA oversight, the compliance burden is shared, and the donor charity isn't responsible for ensuring foreign operations meet Canadian charitable standards.

Pathway Two: Own Activities and Intermediary Arrangements

The second pathway available to Canadian charities is conducting their "own activities" internationally. This approach offers greater control over operations but requires more sophisticated legal and operational structures.

The Challenge of Foreign Partners

Foreign charities and NGOs are rarely qualified donees under Canadian law. This means Canadian charities cannot simply transfer funds to them without proper structural arrangements. The funds must be used for the Canadian charity's own activities, with foreign partners acting as intermediaries rather than recipients.

This distinction is crucial. When a Canadian charity works with a foreign organization, the foreign entity must be helping the Canadian charity fulfill its own charitable purposes rather than receiving funds to pursue its own agenda. The Canadian charity retains ultimate responsibility for the activities and outcomes.

Structured Arrangements for International Work

Canadian charities can employ several different structured arrangements to conduct international operations:

Direct Employee and Volunteer Operations: The most straightforward approach involves Canadian charity employees or volunteers working directly abroad. This provides maximum control and clear accountability but requires significant organizational capacity and resources.

Agency Agreements: Under these arrangements, a foreign organization acts as an agent for the Canadian charity, implementing programs on behalf of the Canadian organization. The foreign entity operates under the Canadian charity's direction and authority, with clear reporting and accountability mechanisms.

Contractor Agreements: Similar to agency arrangements, contractor agreements engage foreign organizations to provide specific services for the Canadian charity's programs. These relationships are typically more transactional and project-specific than ongoing agency relationships.

Joint Venture Agreements: These arrangements involve Canadian charities partnering with foreign organizations to pursue shared charitable objectives. While more complex, joint ventures can leverage the strengths of both organizations while maintaining appropriate oversight.

Cooperative Partnership Agreements: These represent the most sophisticated form of international collaboration, involving ongoing partnerships between Canadian and foreign organizations with shared governance and decision-making structures.

Due Diligence and Oversight Requirements

Regardless of the specific structure chosen, Canadian charities engaging in international operations must maintain appropriate oversight of their activities. This includes conducting due diligence on foreign partners, establishing clear reporting requirements, and ensuring that activities align with the charity's stated purposes.

The CRA expects Canadian charities to maintain control over their international activities, even when working through intermediaries. This means having systems in place to monitor progress, evaluate outcomes, and ensure funds are being used appropriately.

Choosing the Right Approach

The choice between supporting qualified donees and conducting own activities depends on several factors:

Organizational Capacity: Charities with limited international experience or resources may find the qualified donee approach more manageable, while organizations with established international capacity might prefer the control offered by own activities.

Program Objectives: Some charitable goals are better served through direct operations, while others can be effectively achieved through supporting established qualified donees.

Risk Tolerance: Direct international operations involve greater regulatory and operational risks, while qualified donee transfers offer more protection and simplicity.

Geographic Focus: Some regions may have strong qualified donee presence, making that approach more viable, while others may require direct operations or partnerships with local organizations.

Compliance Considerations

Regardless of the approach chosen, Canadian charities must ensure their international activities comply with all applicable laws and regulations. This includes not only Canadian requirements but also the laws of countries where activities are conducted.

Documentation is crucial for both approaches. Charities should maintain clear records of fund transfers, program activities, and outcomes to demonstrate compliance with CRA requirements and accountability to donors.

Regular evaluation and reporting help ensure that international activities remain aligned with the charity's purposes and provide the intended benefits to beneficiaries.

The Path Forward

Canadian charities have significant opportunities to create global impact through both qualified donee transfers and direct international operations. The key is understanding the legal framework and choosing the approach that best fits the organization's capacity, objectives, and risk tolerance.

For organizations new to international work, starting with qualified donee transfers often provides the safest introduction to global charitable activities. As capacity and experience grow, charities can consider more complex arrangements that offer greater control over international operations.

The most important principle is that Canadian charities can and should pursue international charitable work within the established legal framework. With proper planning and compliance, Canadian charitable organizations can effectively address global challenges while meeting all regulatory requirements.

Understanding these pathways enables Canadian charities to make informed decisions about their international engagement, ensuring that their global impact is both effective and legally sound. The framework provides flexibility while maintaining the oversight necessary to protect charitable assets and ensure accountability to donors and beneficiaries alike.

The material provided on this website is for information purposes only.. You should not act or abstain from acting based upon such information without first consulting a Charity Lawyer. We do not warrant the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site. E-mail contact with anyone at B.I.G. Charity Law Group Professional Corporation is not intended to create, and receipt will not constitute, a solicitor-client relationship. Solicitor client relationship will only be created after we have reviewed your case or particulars, decided to accept your case and entered into a written retainer agreement or retainer letter with you.

.png)